1. Columbus Discovered America

Most of us were taught that Christopher Columbus discovered America in 1492, but that’s not quite true. Indigenous people had lived on the land for thousands of years before he arrived, and Leif Erikson, the Norse explorer, actually reached North America around 500 years earlier. Columbus never even set foot on what is now the continental United States, staying instead in the Caribbean. Still, textbooks for decades painted him as the bold pioneer who “found” a new world.

The myth persisted because it was easier to tell schoolchildren a neat, heroic story than to explain the complicated reality. Columbus’s arrival also brought disease, colonization, and violence to the native populations, something early lessons conveniently left out. It took years before schools began including Indigenous voices and perspectives in the retelling of this history. Even now, many still grow up hearing the oversimplified version.

2. Pilgrims and Native Americans Shared a Perfect Thanksgiving

The warm image of Pilgrims and Native Americans sitting side by side, smiling over a shared feast, is one of the most enduring myths. In reality, the 1621 harvest meal was not the peaceful holiday we imagine today. It wasn’t even called Thanksgiving. The meal was more about survival than celebration, and tensions between the two groups didn’t magically vanish after it.

The story of harmony was created centuries later to give Americans a cozy national origin tale. It helped build unity, especially during the Civil War when Abraham Lincoln declared Thanksgiving a national holiday. But this romanticized version brushes past the conflicts, broken treaties, and violence that followed. The real history is far messier and far less heartwarming.

3. George Washington and the Cherry Tree

“Father, I cannot tell a lie.” If that phrase rings a bell, it’s because many kids were taught that George Washington admitted to chopping down a cherry tree when he was six years old. The problem is, the story was invented by a biographer named Mason Locke Weems after Washington’s death. It was never based on fact. Weems created the tale to highlight Washington’s honesty and make him a role model for young Americans.

The myth caught on because it was simple, charming, and easy to pass down in classrooms. It also gave teachers a way to teach honesty without diving into Washington’s actual, more complicated life. By the time people realized it was fake, the story had become too deeply woven into the culture. Many still remember it as if it were true, despite historians debunking it long ago.

4. Betsy Ross Sewed the First American Flag

Generations of schoolchildren grew up picturing Betsy Ross hunched over by candlelight, sewing the very first American flag. But there’s little evidence that she actually made it. The story first surfaced nearly a century later, told by her grandson, and historians haven’t found documentation to back it up. While Ross was indeed a skilled seamstress who worked with flags, the credit for the original design is still disputed.

The tale stuck because it gave the Revolution a relatable, domestic hero in a woman’s face. At a time when history books were filled with male names, Ross’s story added balance and charm. It’s not that she wasn’t important—she contributed plenty—but the image of her stitching up the first Stars and Stripes is more legend than fact. Yet the myth endures because it makes for such a good story.

5. Paul Revere’s Solo Midnight Ride

Most people think Paul Revere galloped alone through the night, shouting “The British are coming!” The truth is, he was part of a network of riders, and he never actually used that famous phrase. Revere warned that “regulars” were coming, since most colonists still considered themselves British. On top of that, he was eventually captured by soldiers before finishing his route. Others, like William Dawes and Samuel Prescott, also played major roles in spreading the alarm.

The solo-hero myth was cemented by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1860 poem, which glorified Revere’s bravery while leaving the others out. The poem became required reading for decades, overshadowing the full story. While Revere was indeed brave, his fame owes more to poetry than to historical accuracy. The ride was a group effort, not a one-man show.

6. The Wild West Was Full of Gunfights

Thanks to Hollywood, many people imagine the Wild West as a place where cowboys settled disputes with dramatic shootouts in the streets. In reality, towns had strict gun laws, and shootouts were extremely rare. Most cowboys spent their time herding cattle, not drawing pistols. Town sheriffs actually enforced rules against carrying firearms in saloons or public places.

The myth stuck because it made for thrilling entertainment. Movies and dime novels loved dramatizing gunslingers and duels, painting the frontier as lawless and chaotic. Real life was far more about long, grueling workdays and survival in harsh conditions. The handful of gunfights that did happen were blown up into legend, creating a lasting but false image of the Old West.

7. The Alamo Was a Noble Fight for Freedom

School lessons often paint the Battle of the Alamo as a fight for freedom and independence. While it’s true the defenders were brave, the story leaves out the fact that many were fighting to preserve slavery. Mexico had already outlawed slavery, and the push for Texas independence was partly fueled by Anglo settlers wanting to keep the practice alive. The simplified version of “heroes against tyrants” ignores this uncomfortable truth.

The myth endures because the story of heroic last stands appeals to people’s emotions. It became a rallying cry for Texan pride and later American identity. Films, monuments, and slogans like “Remember the Alamo” turned the battle into a symbol of courage, even if the full context was lost. What remains in most textbooks is a sanitized version of a much more complicated event.

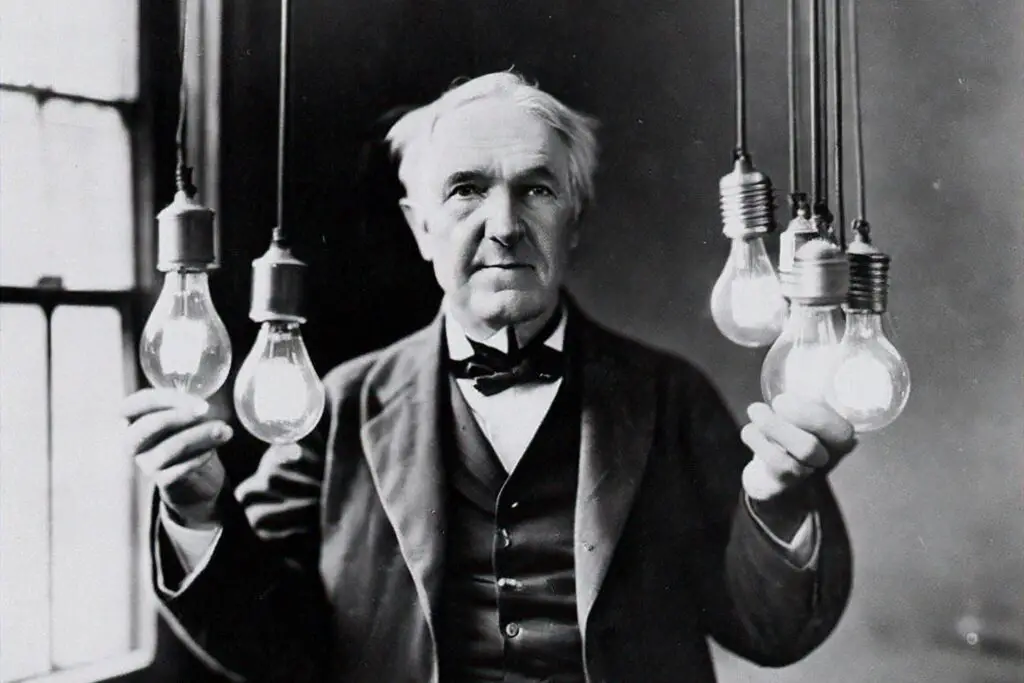

8. Thomas Edison Invented the Light Bulb

Thomas Edison is often credited with inventing the light bulb, but he wasn’t the first. Several inventors, including Humphry Davy and Joseph Swan, had already created earlier versions. What Edison did was improve the design, making it practical and long-lasting for everyday use. He also had the business savvy to patent and promote his version, ensuring his name became linked to the invention.

The myth of Edison as the sole genius inventor fits the American ideal of innovation and individual brilliance. In reality, most breakthroughs were collaborative, built on years of work by many people. Textbooks rarely emphasized those other names, making Edison the face of the light bulb. It’s not untrue that he played a key role, but it’s misleading to say he invented it from scratch.

9. The Gold Rush Made Everyone Rich

The image of miners striking it rich with gold pans in California is a classic part of American lore. But the truth is, very few actually became wealthy from gold. Most miners left disappointed or broke, while many businesses that sold supplies and services to miners made fortunes. People like Levi Strauss, who created durable jeans for miners, ended up richer than most who dug in the dirt.

The myth stuck because stories of instant wealth inspired more people to chase their fortunes. It also helped attract settlers westward, fueling expansion. The hardships, failed claims, and broken dreams weren’t as glamorous as the idea of nuggets waiting in rivers. The Gold Rush did change America, but not in the way textbooks often made it sound.

10. Salem Witches Were Burned at the Stake

A chilling part of American history, the Salem Witch Trials are often remembered with images of women being burned alive. The truth is, none of the accused in Salem were burned at the stake. Most were hanged, one man was pressed to death with heavy stones, and several died in prison. Burning witches was a European practice, but it didn’t happen in colonial Massachusetts.

The mix-up may come from blending European and American witch lore. Over time, people lumped all witch trials together in one terrifying image. The actual events in Salem were horrific enough without exaggeration. Still, the burned-at-the-stake myth lingers in popular imagination and even makes it into classrooms now and then.

11. Vikings Wore Horned Helmets

Textbooks and illustrations once loved showing Vikings with horned helmets, charging into battle. But archeological evidence shows no such helmets were ever used. The horned look came from 19th-century artists and costume designers who wanted to make Vikings appear more dramatic and barbaric. The idea spread so widely that it became hard to separate fact from fiction.

While this myth is more European than strictly American, it seeped into American classrooms and culture. Textbooks borrowed the same images, and kids grew up imagining Vikings as horned warriors. In truth, Viking helmets were practical and simple, built for battle, not flair. Yet the false image endures because it’s just too striking to forget.

12. America Was Always a Melting Pot of Equality

The phrase “land of opportunity” made its way into lessons that suggested America always welcomed everyone equally. While the country was built by immigrants, many groups faced harsh discrimination when they arrived. Irish, Italian, Chinese, and other communities were often treated as outsiders. Textbooks smoothed over those struggles to create a patriotic, unifying image.

The myth persists because it supports the narrative of America as uniquely open and free. The truth is, the road to equality has been long and uneven. Each wave of newcomers faced challenges, protests, and even laws designed to keep them out. While progress has been made, the idea that America was always a fair melting pot is more myth than fact.

13. The Civil War Was About States’ Rights

Many textbooks once taught that the Civil War was fought mainly over states’ rights, but they often left out the central issue—slavery. Southern states seceded because they wanted to preserve the institution of slavery, plain and simple. The “states’ rights” argument came later as a way to soften or obscure the truth. Textbooks, especially in the South, leaned heavily on this version for decades.

The myth lasted because it allowed generations to avoid confronting the brutality of slavery head-on. It also made the Confederacy’s cause seem more noble than it was. Only in more recent years have textbooks begun to highlight slavery as the main cause. Still, the states’ rights narrative continues to be repeated by those uncomfortable with the real history.