1. Pinsetter

Before automatic pinsetters took over, bowling alleys hired teenagers to reset the pins by hand. They perched on a little seat at the back of the lane, waiting for the ball to thunder through. Then they hopped down to clear the fallen pins, rerack the triangle, and send the ball back on its return path. Quick reflexes mattered, because a mistimed move could meet a rolling ball or a flying pin.

Many handled two lanes at once, answering shouts from bowlers and the nonstop clatter of wood. Pay was a few coins per game, plus tips, which made league nights the best nights. When Brunswick and AMF machines swept the industry in the ’50s and ’60s, the job vanished almost overnight. Now it survives mostly as a fun bit of bowling history and the occasional story from someone’s first job.

2. Leech Collector

When bloodletting was considered a cure for just about everything, someone had to round up the leeches. Collectors waded into ponds and marshes, letting the little hitchhikers latch on so they could peel them off into jars. It was soggy, cold, and often left people with infected cuts that took weeks to heal. Payment was usually by the jar, so knowing the right bogs mattered.

Some coaxed faster results by tying raw meat to their ankles, which is as grim as it sounds. Salt and sand were standard tools for persuading stubborn leeches to let go. Apothecaries and hospitals were steady customers, especially during outbreaks. As medical science moved on, the marshes got a lot quieter.

3. Lamplighter

Before electric bulbs, evenings depended on a person walking the streets with a ladder and a flame. Lamplighters opened tiny hatches, lit the gas mantles, and made sure each globe was clean enough to shine. They memorized long routes and kept a steady pace, because whole neighborhoods counted on them. At dawn they returned to snuff everything out, ready to repeat it all the next night.

Stormy weather turned the job into a slippery obstacle course. Sooty glass meant extra cleaning and a few grumbles from residents if it was missed. Once electric grids grew reliable, the nightly ritual faded into ceremony. A few historic districts still do it for tradition and a little city magic.

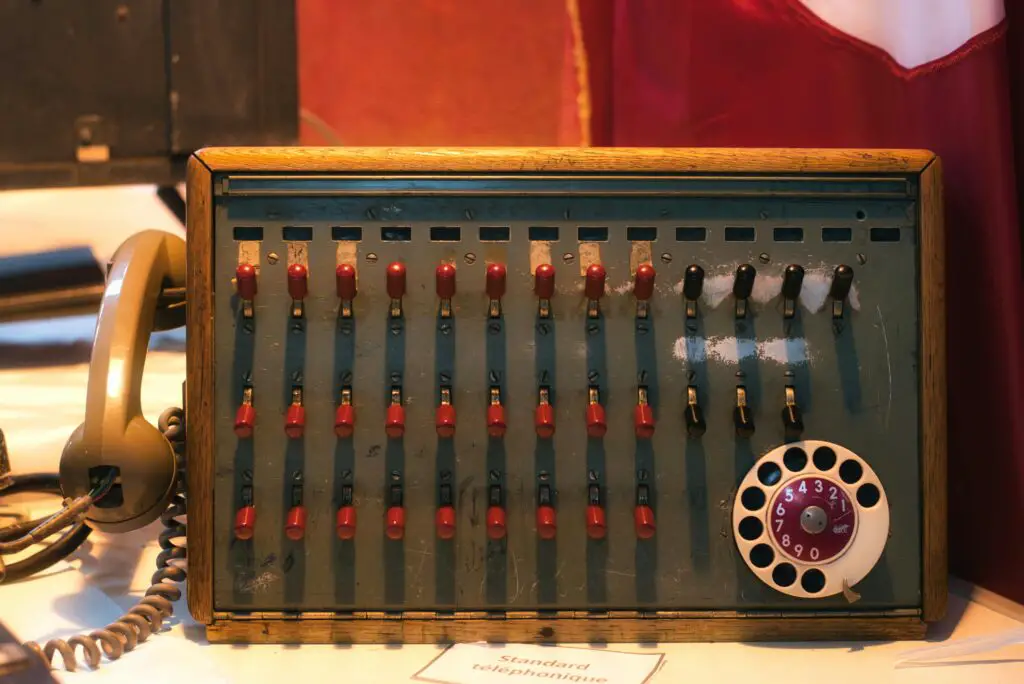

4. Switchboard Operator

Early phone calls did not just travel by wire, they traveled through a person’s hands. Switchboard operators sat before a wall of jacks and cords, answering with a crisp greeting and patching callers to the right line. They remembered familiar voices, local gossip, and the best way to route a crackly connection. Efficiency mattered, but so did courtesy, because the operator was the town’s telephone face.

Busy hours sounded like a hive, with cords flying and lights blinking in endless patterns. Wrong numbers and party lines created moments of comedy that everyone pretended not to hear. Automated exchanges slowly replaced the cords and human memory. The quiet that followed felt almost eerie after years of chatter.

5. Iceman

Before refrigerators were standard, cold came as a weekly delivery. The iceman hauled blocks from insulated trucks, crushed them to size, and slid them into iceboxes with a practiced thump. Apartments marked their windows with cards showing how many pounds they needed. Summer meant long, sweaty days and grateful customers hovering in kitchens.

Kids chased the wagon for slivers on hot afternoons, like a frosty treat that barely lasted. Meltwater dripped down stairwells and left trails across sidewalks. As electric refrigerators spread in the ’20s and ’30s, the route cards vanished from windows. The job slipped away with the last clink of tongs.

6. Lector

In cigar factories, workers rolled leaves by hand for hours, eyes down and fingers busy. A lector stood on a platform and read aloud to keep minds engaged, choosing everything from newspapers to novels and political speeches. The best lectors had showmanship, voices that carried, and a knack for picking cliffhangers. Pay often came directly from the workers who passed the hat.

Managers sometimes bristled at fiery editorials stirring up debate on the floor. Even so, the tradition created shared culture and inside jokes that traveled home after the whistle. Recorded radio and changing factory rules pushed the lector off the platform. The silence that replaced him was efficient and just a little dull.

7. Town Crier

Before newspapers were cheap and radios were common, the news walked on two feet. The town crier rang a bell, planted himself at a busy corner, and shouted the latest proclamations, markets, and gossip. People gathered for weather warnings, lost-and-found notes, and announcements from the mayor. If you missed a reading, someone would retell it over supper.

Criers needed a strong voice, a sturdy presence, and a memory that did not falter under questions. They also served as a kind of community moderator, urging calm when rumors ran hot. As print and broadcasting took over, the bell got quieter. Today the role shows up mostly in parades and period festivals.

8. Linotype Operator

Hot metal printing brought words to life with speed that felt like sorcery. Linotype operators sat at clacking keyboards that cast entire lines of type in molten lead, then stacked those lines into pages. The work demanded rhythm, accuracy, and fingers that danced without staring at the keys. A good operator could keep a newsroom on deadline and a foreman smiling.

But the machines were loud, heavy, and always a little dangerous. Ink, heat, and lead shavings gave the shop its unmistakable smell. Phototypesetting and digital layout arrived, and the metal cooled for good. Newspapers lost a sound that once defined the building.

9. Human Computer

Before electronic computers, complex math had a human face. Teams of human computers, often women, filled notebooks with calculations for astronomy, engineering, navigation, and early rocket work. They checked each other’s figures and built systems to catch tiny errors. The work was meticulous, quiet, and essential to big discoveries.

Slide rules and mechanical aids helped, but patience helped most. A single wrong digit could ruin hours of effort and a scientist’s schedule. As electronic machines took over, many human computers retrained into programming. The job title vanished, while their fingerprints stayed on history.

10. Rat Catcher

Cities needed pest control long before modern traps and services. Rat catchers worked at night with dogs, sacks, and quick hands, tracking nests in alleys, docks, and cellars. Some used smoke or ferrets to flush the pests, then counted the haul for municipal pay. It was grimy, smelly, and strangely competitive work.

Public health officials relied on them during outbreaks tied to vermin. The best catchers knew how to read gnaw marks like detectives read footprints. Better sanitation and regulated pest control pushed the trade into the past. Today it sounds like a tall tale, but it kept bread shops and warehouses in business.

11. Gong Farmer

Medieval towns had a sanitation job that no one envied and everyone needed. Gong farmers climbed into cesspits and privies at night to shovel waste into carts, then hauled it outside the walls. The work paid well for the time, likely because the hazards were obvious. Smell clung to clothes, tools, and reputations that were hard to escape.

They learned which streets to avoid by daylight and which neighbors paid on time. A quick pace mattered because overflowing pits brought fines and angry landlords. As sewers and modern plumbing spread, the nightly rounds ended. History kept the name, partly for the shock value and partly out of respect for a rough necessity.

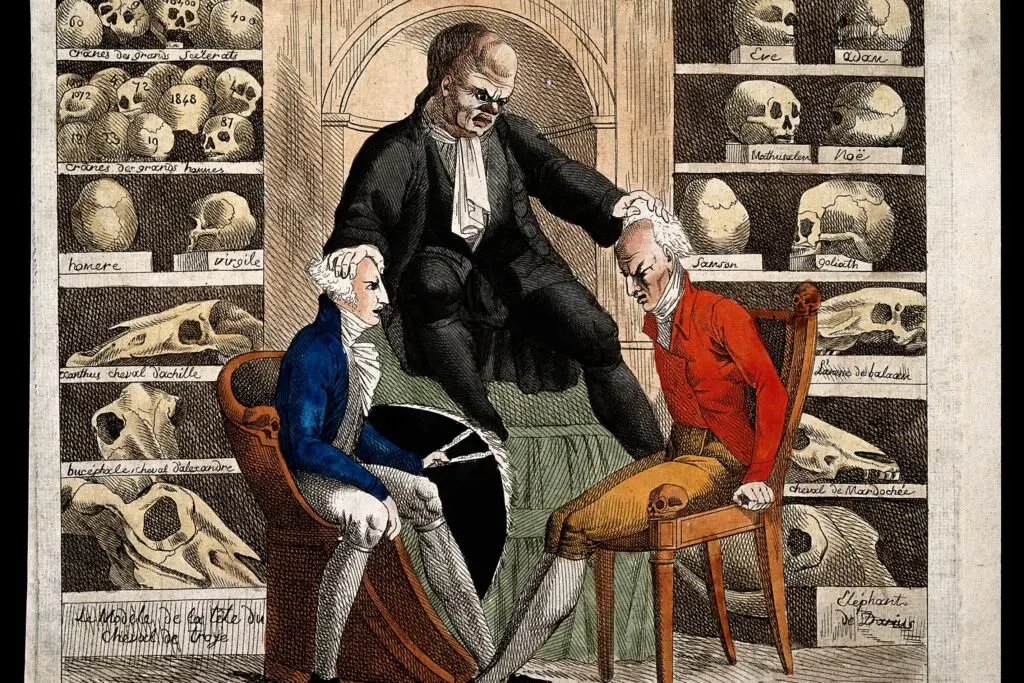

12. Phrenologist

In the 19th century, earnest practitioners claimed your skull bumps revealed your mind. Phrenologists measured heads with calipers, drew elaborate charts, and offered life guidance from the results. Parlors displayed brass instruments and busts labeled with virtues and vices. It felt scientific to customers who wanted answers wrapped in numbers.

Real neuroscience eventually showed the method had no foundation. Museums kept the curio pieces, and the charts migrated to novelty shops. The profession evaporated, but the language lingered in jokes about someone having a big head. It is a perfect example of how quickly serious-sounding ideas can become historical footnotes.