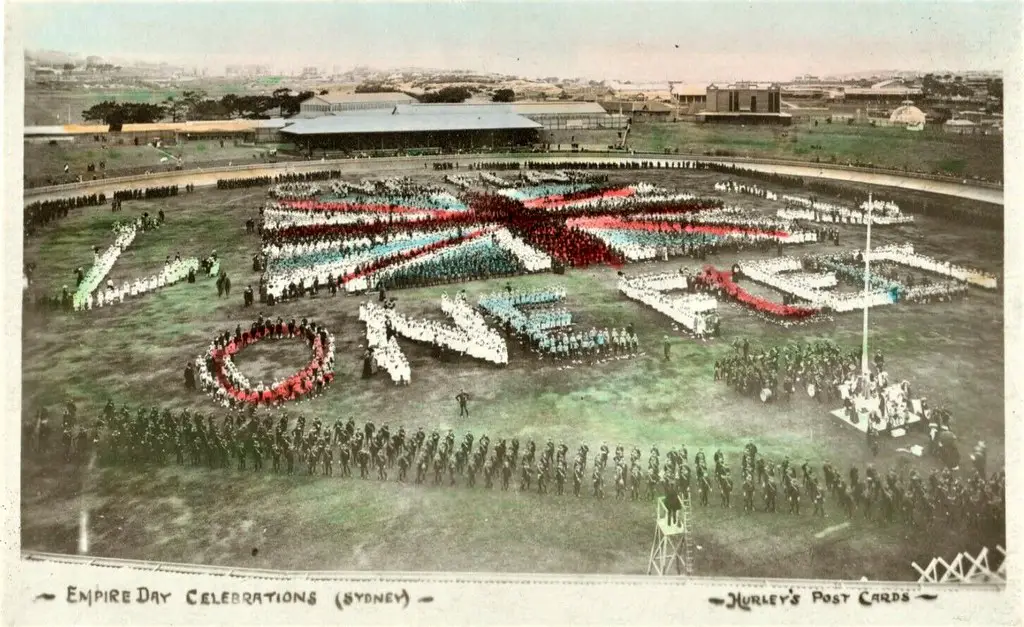

1. Empire Day

Empire Day was once a huge deal in Britain and its colonies, celebrated every May 24 to honor Queen Victoria’s birthday and the British Empire. Schools would hold parades, kids waved flags, and patriotic songs filled the air. The day was meant to instill loyalty to the Crown and pride in being part of something global. For children, it often meant a half-day off school, which might have been the best part.

As time went on, though, the empire itself began to shrink, and the holiday lost its meaning. By the mid-20th century, people weren’t as eager to celebrate imperialism. In 1958, Empire Day officially became Commonwealth Day, but even that faded from public attention. These days, most people in the UK hardly notice when it rolls around.

2. May Day (as a major holiday)

May Day used to be a colorful festival in many European countries, full of dancing around maypoles, crowning a May Queen, and celebrating the arrival of spring. Villages would come alive with flowers, music, and pageantry. For centuries, it was one of the most joyful community events of the year. Children and adults alike looked forward to it as a chance to welcome warmer days.

But as industrialization spread, the holiday lost steam. Factories didn’t close for maypole dancing, and towns became less interested in old traditions. In some countries, May Day shifted into a labor rights holiday instead, losing its festive flair. Today, outside of a few reenactments, the bright ribbons and May Queens have largely disappeared.

3. Evacuation Day

Evacuation Day was once a proud holiday in New York City, commemorating November 25, 1783, when the British finally left Manhattan after the Revolutionary War. For nearly a century, parades, speeches, and fireworks marked the occasion. It was especially meaningful to Revolutionary War veterans who saw it as the true end of foreign rule.

Over time, though, Evacuation Day was overshadowed by Thanksgiving, which was set just days earlier. By the late 1800s, most New Yorkers had stopped celebrating it. Only a handful of neighborhoods kept it alive into the 20th century. Today, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who remembers this once-patriotic day.

4. St. Crispin’s Day

Back in medieval times, St. Crispin’s Day on October 25 celebrated the patron saint of cobblers, tanners, and leather workers. The holiday honored craftsmanship, with guilds holding feasts and processions. It also had a patriotic tinge in England, thanks to Shakespeare’s famous speech in Henry V about the Battle of Agincourt, which took place on that date.

As guild culture faded and industrial work took over, the holiday’s meaning dwindled. Shoe factories didn’t bother closing for celebrations. By the modern era, it was remembered more for Shakespeare than for any real festivities. What was once a day of pride for tradespeople is now just a footnote in history.

5. Decoration Day

Before Memorial Day existed, Americans celebrated Decoration Day, which began after the Civil War. Families would visit cemeteries, bringing flowers to decorate soldiers’ graves. It was a solemn but hopeful tradition, uniting people in remembrance of those lost. Communities across the country observed it, often with parades and speeches.

Eventually, the name shifted to Memorial Day, which became a federal holiday in 1971. The spirit stayed the same, but Decoration Day itself vanished. For older generations, the original name carried a personal connection. Today, hardly anyone uses the term, though its roots are still alive in Memorial Day rituals.

6. Ragamuffin Day

Long before Halloween became the candy-fueled event we know, Ragamuffin Day was the big day for kids in New York. Every Thanksgiving, children dressed up in costumes, often ragged clothes or masks, and went door-to-door asking for treats. It was rowdy and fun, though parents sometimes complained about the chaos.

By the 1930s, the tradition started to fade as Thanksgiving parades grew in popularity. Halloween, with its spookier costumes and better candy, eventually took over. Ragamuffin Day lived on in some neighborhoods until the 1950s, but it’s almost completely forgotten now. What was once a quirky urban tradition is now just a historical curiosity.

7. Whitsun

Whitsun, short for Whitsunday, was once one of the most important Christian holidays in England. It celebrated the feast of Pentecost, and towns marked it with fairs, church services, and sporting events. In some places, it rivaled Christmas in scale. Children looked forward to special food and community gatherings.

In the 1970s, the UK government shifted the holiday to a generic “Spring Bank Holiday.” Without its religious connection, Whitsun quickly faded from public memory. People still enjoy the long weekend, but the old customs are gone. What was once a highlight of the year is now just another bank holiday with no special meaning.

8. Armistice Day

November 11 was originally Armistice Day, commemorating the end of World War I in 1918. In the U.S., it was a solemn holiday with parades and moments of silence to honor veterans and the hope for peace. For many families, it carried deeply personal meaning.

In 1954, the U.S. renamed it Veterans Day to honor veterans of all wars. While the holiday still exists, the specific focus on World War I has vanished. Armistice Day itself is gone, remembered only by historians and those who study the Great War. It’s a reminder of how holidays can evolve and lose their original context.

9. Candlemas

Every February 2, people once celebrated Candlemas, marking the presentation of Jesus at the Temple. It involved candle blessings and processions, and in some cultures, it was a way to look ahead at the coming of spring. Long before Groundhog Day, Candlemas had its own weather lore attached to it.

As secular traditions grew, Candlemas faded in importance. Groundhog Day, oddly enough, took its place in the U.S., borrowing from similar European superstitions. Today, Candlemas is still marked quietly in some churches but is hardly a cultural event. Most people have no idea the holiday even existed.

10. Pope’s Day

In colonial New England, Pope’s Day was a wild anti-Catholic holiday celebrated every November 5. Crowds paraded through towns, burning effigies of the Pope in bonfires. It was rowdy and often violent, with rival gangs clashing in the streets. Despite its ugly roots, it was a major annual event in places like Boston.

After the Revolution, though, Pope’s Day quickly died out. Americans wanted unity, not division, and George Washington himself discouraged the practice. By the early 1800s, it had disappeared entirely. It’s now remembered as an example of how some traditions were left behind for good reason.

11. Labor Thanksgiving Day (U.S. version)

In the 19th century, some American labor groups celebrated their own version of Thanksgiving, separate from the national holiday. It was called Labor Thanksgiving Day, and it honored workers’ rights, fair wages, and solidarity. The day often included parades, picnics, and speeches by union leaders.

But as Labor Day became the recognized workers’ holiday, Labor Thanksgiving faded away. The idea merged with existing celebrations, leaving only one Thanksgiving on the calendar. While Japan still observes a holiday by that name, Americans have long forgotten theirs. What once symbolized worker pride is now just a historical footnote.

12. Eel Day

Believe it or not, some towns in England once had an annual “Eel Day,” celebrating the importance of eels as a food source. River communities marked the season with feasts, games, and fairs, often tied to fishing traditions. Eels were a staple food, and the day was both practical and fun.

As diets changed and eels became less common, the holiday disappeared. Supermarkets don’t exactly have an eel aisle, and most people wouldn’t consider them a treat today. Some places have tried to revive Eel Day as a quirky tourist attraction, but it’s no longer the beloved tradition it once was. What was once essential has slipped into obscurity.