1. Salt Pork

Salt pork was a staple for sailors, soldiers, and rural families, but it wasn’t exactly a treat. It was essentially fatty pork belly packed in barrels of salt until it turned tough and briny, with a texture somewhere between shoe leather and candle wax. You had to soak it for hours to make it even remotely edible, and even then, it was overwhelmingly salty.

The long storage time meant the meat could become rancid, especially in hot weather, and the heavy salt could make you desperately thirsty. Cooking it usually meant boiling it into stews or frying it with other bland staples like hardtack. Nutritionally, it was a reliable source of fat and calories, but flavor-wise, it left much to be desired. Imagine eating it day after day without the option of a fresh salad in sight.

2. Hardtack

Hardtack was a simple biscuit made of flour, water, and sometimes salt, baked until it was rock hard. It could last for years without going bad, which made it ideal for long voyages and military campaigns. Unfortunately, the texture could be so tough you’d need to soak it in coffee or soup just to avoid breaking a tooth.

Many pieces were infested with weevils after long storage, and soldiers would knock the biscuits on the table to get the bugs out before eating. Even without the insects, the taste was bland to the point of being depressing. For people in the 1800s, it was a survival food, but for modern appetites, it’s hard to imagine choosing it over even the most basic bread.

3. Pickled Eggs

Pickled eggs were a popular snack in taverns and farmhouses, preserved in vinegar for months at a time. While that meant they were safe to eat long after being laid, the texture turned rubbery and the flavor was sharp enough to make your eyes water. For many, they were more about practicality than pleasure.

The acidic brine often took on strange colors from added spices like turmeric or beet juice. After weeks in the jar, the eggs could absorb so much vinegar that the yolk became dry and crumbly. They were protein-packed and easy to store, but the sensory experience was not for the faint of heart.

4. Calf’s Foot Jelly

This dish was made by boiling calf’s feet for hours until the natural gelatin leached out, then straining and cooling it into a wobbly mold. Sometimes sweeteners and spices were added, turning it into a dessert of sorts. To modern tastes, the thought of eating gelatin extracted from animal joints might be a little unsettling.

It was prized in the 1800s for its supposed health benefits and was often given to invalids or new mothers. The texture could be slimy, and the flavor was faintly meaty even under sugar and nutmeg. For people back then, it was a restorative food; for us today, it might be an instant appetite killer.

5. Opossum Stew

In rural areas of the American South, opossum was considered fair game for the stew pot. The meat was often described as greasy with a gamey flavor, and recipes frequently advised parboiling it to remove “wild” taste before cooking it with vegetables. Still, it was a cheap source of protein for families with limited options.

Because opossums were scavengers, there was always debate about whether their meat was safe or pleasant to eat. The long cooking times and heavy seasoning were meant to disguise its less appealing qualities. While it was a practical meal in the 1800s, most modern diners wouldn’t be lining up for a bowl.

6. Mincemeat (with Actual Meat)

Today, mincemeat pies are often just fruit and spices, but in the 1800s, the “meat” part was very real. Beef or mutton was minced and mixed with dried fruits, suet, spices, and sometimes brandy, then baked into pies. The combination of sweet and savory could be intense, especially when the meat had been preserved for a while.

The rich, oily suet helped the pie last through the winter, but it also gave it a heavy mouthfeel. For people used to sugar desserts, biting into a raisin-filled pie that also contained chunks of beef could be an unpleasant surprise. Back then, it was a seasonal tradition; now, it’s more likely to raise eyebrows than cravings.

7. Tripe

Tripe is the lining of a cow’s stomach, cleaned and boiled until tender, then often served in soups or fried. In the 1800s, it was cheap and widely available, especially in working-class neighborhoods. The chewy texture and mild but unmistakably “barnyard” aroma could be off-putting to those unaccustomed to it.

Preparation often involved hours of simmering to make it palatable, and it was sometimes served with vinegar or heavily seasoned gravy to mask the smell. For those with limited meat options, it was a practical choice, but it’s easy to see why many modern eaters would pass.

8. Eel Pie

Eels were abundant in rivers and coastal waters, and their firm, oily flesh made them a common protein source in the 1800s. Eel pie consisted of chopped eel baked in pastry with a thick, savory sauce. While nutritious, the flavor could be strong and slightly fishy, not appealing to everyone.

The preparation process—skinning and cleaning the eels—wasn’t for the squeamish. In some regions, the pie might be served cold, with a gelatin layer formed from the cooking juices. While it was beloved by many in its time, for modern palates, the idea of eel encased in pastry might not be a winning dinner option.

9. Boiled Mutton

Boiled mutton was a mainstay in Britain and its colonies, often served with root vegetables and a watery broth. The slow boiling made the meat tender, but also leached out much of its flavor, leaving it bland and gray in color. Without rich sauces, it could be an unappetizing sight on the plate.

It was cheap and could feed a large family, which made it popular among the lower and middle classes. However, the smell during cooking could be strong and lingering, and the texture was not always appealing. While it filled stomachs, it rarely made anyone’s list of favorite meals.

10. Souse

Souse was made by pickling pig’s feet, ears, or other scraps in a vinegar brine, sometimes with onions and spices. Served cold, it had a gelatinous texture from the collagen in the meat. The tangy, chewy bites were a common way to use every part of the animal.

For people in the 1800s, it was both thrifty and a source of protein, especially in rural areas. For modern eaters, the combination of cartilage, vinegar, and cold fat might be a quick appetite deterrent. Its strong smell alone could turn away the uninitiated.

11. Head Cheese

Despite its name, head cheese isn’t dairy—it’s a terrine made from the head meat of a pig or calf, set in its own gelatin. In the 1800s, it was a way to preserve meat without refrigeration, often served in slices with bread. The mix of textures, from tender meat to chewy bits, was not for everyone.

It was considered a delicacy in some areas, but the process of making it—boiling a whole animal head—was enough to put some people off. Even once prepared, its jellied appearance and cold temperature could make it seem less than inviting. Today, it’s a rarity, but back then, it was a frugal and practical dish.

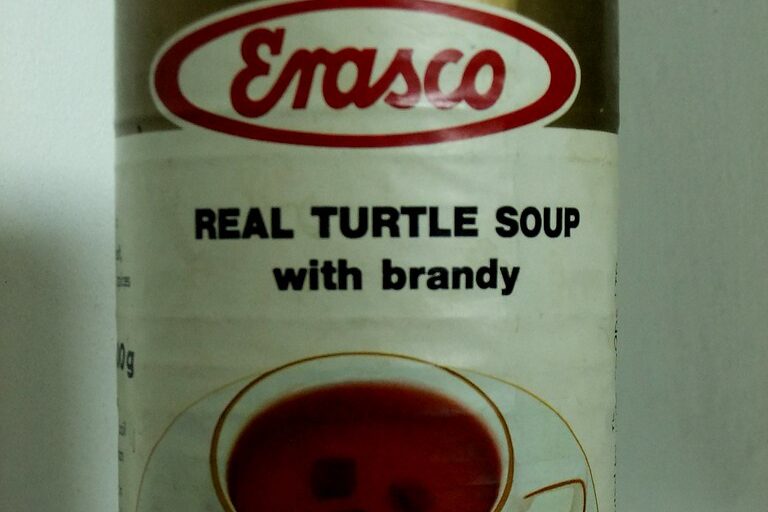

12. Mock Turtle Soup

Mock turtle soup was invented as a cheaper alternative to green turtle soup, which was a luxury. It used calf’s head, feet, and sometimes other organ meats to replicate the gelatinous texture and rich flavor of turtle meat. The broth was often darkened with burnt sugar and flavored with sherry.

While it was a clever substitute, knowing that you were eating boiled calf’s head might have been enough to make some diners hesitant. The preparation was labor-intensive and the result was rich but also heavy. For those accustomed to it, it was a treat; for the rest of us, it might be a hard pass.