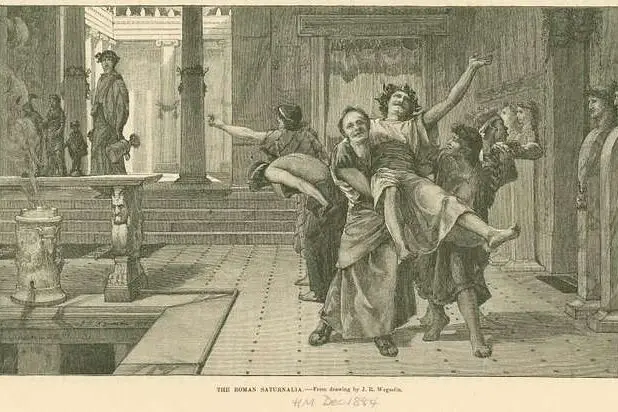

1. The Roman Saturnalia

The Roman Saturnalia, celebrated in honor of the god Saturn, was one of the most raucous festivals in ancient Rome. Held every December, it involved role reversals, where masters served their slaves, and the usual social order was turned upside down. People would exchange gifts, wear disguises, and indulge in feasting and drinking, creating an atmosphere of carefree abandon. It was a time when public morality was set aside in favor of pure revelry.

Despite its popularity, the festival’s unruly nature became a point of concern for later authorities. By the time of the Roman Empire’s decline, the festival’s excesses were seen as a threat to societal order. Eventually, it was suppressed, and its practices were integrated into what we now know as Christmas celebrations, though with much more restraint.

2. The Greek Dionysia

The Dionysia was a festival dedicated to Dionysus, the god of wine, fertility, and ecstatic revelry. Held in Athens, it included theatrical performances, processions, and the consumption of large quantities of wine. It was a time for the community to come together in both creative expression and uninhibited celebration, often pushing the boundaries of social norms.

However, as Greek society became more structured, the disorderly nature of the festival started to be frowned upon. The unchecked drunkenness and orgiastic behaviors led to a clampdown on such festivities, especially as the Roman Empire spread and imposed stricter laws. The Dionysia eventually faded, though it left a legacy in the form of Western theater.

3. The Viking Yule Feast

The Viking Yule Feast was a midwinter festival that celebrated the rebirth of the sun. Known for its feasting, toasts, and the burning of a massive Yule log, the festival was a time for community bonding and honoring the gods. Vikings would indulge in beer, mead, and food, and the festival often included sacrifices to ensure the gods’ favor for the coming year.

As Christianity spread through Scandinavia, the Yule Feast became associated with pagan practices that the church sought to eliminate. The feasting and revelry were deemed too wild, and over time, the Christianized version of Christmas took its place. Still, some aspects of the Yule Feast, like the Yule log and festive gatherings, endured in a modified form.

4. The Roman Lupercalia

Lupercalia was an ancient Roman festival held in mid-February, celebrated to ward off evil spirits and promote fertility. The festivities involved a peculiar mix of animal sacrifices, feasting, and physical acts like whipping young women with strips of goat hide. The goal was to promote fertility and purification, and the festival often led to spontaneous matches between lovers.

The wild nature of Lupercalia, particularly the whipping and its ties to fertility rites, made it a target for Christian reformers. By the end of the 5th century, Pope Gelasius I formally banned the festival, deeming it too pagan and sexually charged. Though the tradition of love and romance continued, Lupercalia was replaced with the more subdued Valentine’s Day.

5. The Egyptian Festival of Opet

The Festival of Opet was an ancient Egyptian celebration held in Thebes to honor the god Amun. During this festival, statues of the gods were paraded from the temple of Karnak to the temple of Luxor, marking a sacred journey. The festival was filled with music, dancing, feasting, and much revelry, as people celebrated the fertility of the land and the blessing of the gods.

Over time, as Egypt’s power waned, the lavish and sometimes debauched celebrations were seen as too extravagant for a more controlled and formalized society. The shift in religious and political views led to the gradual decline of the festival, which was eventually replaced by more regulated religious observances. The tradition of grand religious festivals persisted, but the unchecked revelry was reined in.

6. The Roman Bacchanalia

The Bacchanalia, named after Bacchus, the Roman god of wine and revelry, was a festival that grew infamous for its wild and frenzied nature. Initially held only in the countryside, the festival eventually spread to the city of Rome, where it became known for its excessive drinking, orgies, and secretive rites. Participants believed that by surrendering to Bacchus, they would experience ecstasy and connection to the divine.

In the 2nd century BCE, the Roman Senate, alarmed by the festival’s increasing influence and potential for social unrest, banned the Bacchanalia. They saw it as a destabilizing force that could undermine the moral fabric of Roman society. Though it never fully disappeared, the Bacchanalia was forced underground, and its wild abandon became a symbol of what the Romans had once considered too dangerous to tolerate.