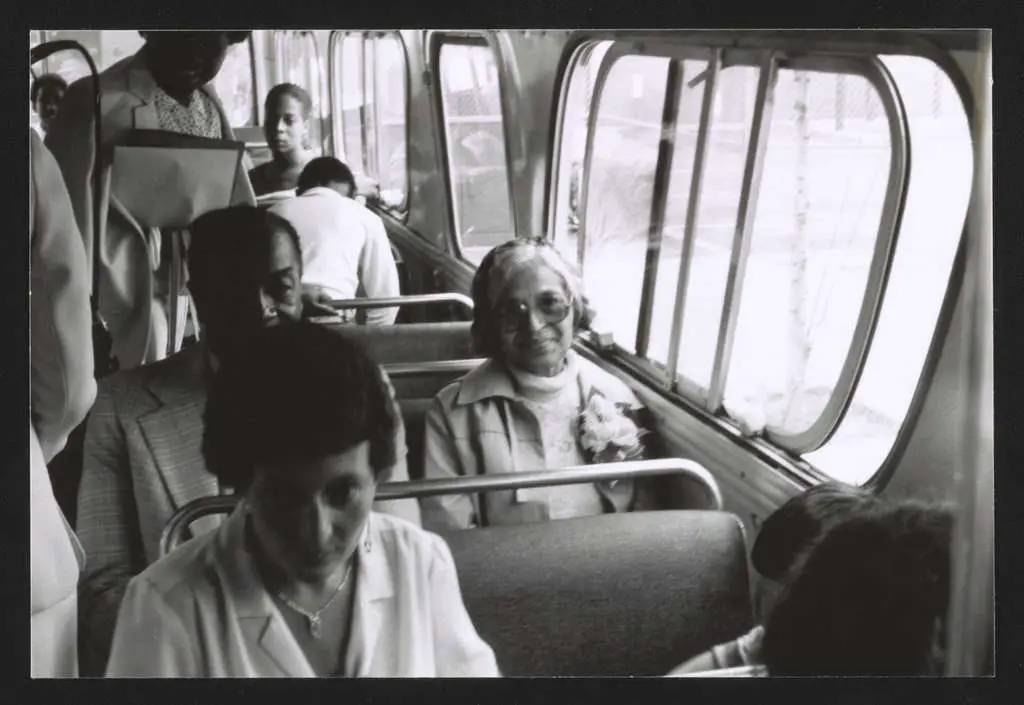

1. Rosa Parks Redefined Resistance Beyond the Bus

Rosa Parks is often remembered for her brave stance on a Montgomery bus in ‘55, but her activism didn’t stop there—it only grew stronger in the ‘60s. She was a field representative for the NAACP and worked alongside leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and John Conyers to push for civil rights legislation. Parks also helped investigate cases of racial violence, ensuring that the stories of Black victims were not buried. She spent much of the ‘60s advocating for fair housing in Detroit, where redlining and discrimination were rampant says WXYZ. Even when she struggled financially, Parks never wavered in her commitment to justice. Her presence at key protests, including the March on Washington, kept her at the center of the movement. Though she was soft-spoken, her impact was anything but small. Parks also fought for Black political representation, helping Conyers win a seat in Congress. Her home became a safe space for young activists looking for guidance. She championed the rights of Black women, especially domestic workers, whose struggles were often overlooked.

Parks knew the fight wasn’t just about buses—it was about dignity, fair wages, and safety for Black people everywhere. She worked behind the scenes to provide support to lesser-known activists, particularly women who faced double discrimination. Even after the Civil Rights Act of ‘64, she continued pushing for economic justice, knowing that legal victories didn’t always translate into real change. Her work with the Detroit chapter of the Black Power movement in the late ‘60s showed her evolving activism. Parks was also deeply invested in criminal justice reform, advocating for the release of political prisoners. She never sought the spotlight, yet her influence was undeniable. The Black Panther Party even acknowledged her as a revolutionary role model. Parks lived activism every day, proving that fighting for justice was a lifelong commitment. By the time the ‘60s ended, she had cemented herself as more than just a bus protester—she was a strategist, organizer, and mentor. Her impact stretched far beyond Montgomery, touching lives nationwide.

2. Fannie Lou Hamer Made Voting a Personal Battle

Fannie Lou Hamer didn’t just talk about voting rights—she put her life on the line for them. After being fired from her job for attempting to register to vote in ‘62, she turned her struggle into a movement. She co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) in ‘64 to challenge the all-white Democratic delegation in her state. Her speech at the Democratic National Convention that year shook the nation, as she detailed the brutal beatings she endured just for wanting to vote. President Johnson even interrupted her televised speech out of fear it would sway public opinion—but the nation still listened. Hamer’s words forced America to confront the harsh realities of voter suppression in the South. She also organized Freedom Summer, a campaign that brought students and activists to Mississippi to register Black voters. Despite countless death threats, she refused to back down. Hamer believed that political participation was the key to Black liberation, and she spent the decade proving it explains USA Today.

Beyond voting, Hamer tackled economic injustice by starting the Freedom Farm Cooperative in ‘69. She saw how poverty and disenfranchisement were intertwined, and she worked to give Black families control over their own food sources. Her activism wasn’t just about fighting oppression—it was about building self-sufficiency. Hamer also spoke out about the forced sterilization of Black women, a cruel practice known as the “Mississippi appendectomy.” She demanded healthcare justice, knowing that bodily autonomy was part of the civil rights struggle. Though she was often excluded from mainstream leadership circles, her influence was undeniable. Her grassroots organizing helped shift power back to the people, where she believed it belonged. Hamer never let fear silence her, and she made sure others found their voices too. Her famous words, “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired,” became a rallying cry for justice. The ‘60s may have ended, but her impact continued for decades.

3. Dorothy Height Elevated Black Women’s Voices in Leadership

Dorothy Height knew that civil rights and women’s rights were inseparable, and she spent the ‘60s making sure both were part of the conversation. As president of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW), she pushed for Black women to have a seat at the table in major policy discussions. While male leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X were often at the forefront, Height worked behind the scenes to ensure women’s contributions weren’t erased. She played a key role in organizing the March on Washington, even though she wasn’t given the same recognition as male leaders. Her work with the YWCA helped integrate their facilities and make them a force for racial justice says WTVR. Height also traveled internationally, building alliances with women’s movements across Africa and the Caribbean. She was a master negotiator, bridging gaps between civil rights groups and feminist organizations.

In the late ‘60s, she turned her attention to economic empowerment, launching programs that helped Black women find stable jobs and financial independence. She knew that breaking racial barriers wasn’t enough—Black women needed economic freedom too. Height advocated for affordable childcare, fair wages, and leadership training for Black women. She was also instrumental in pushing the government to recognize the struggles of Black women in poverty. Even with limited media coverage, she remained one of the most influential voices of her time. Her ability to navigate male-dominated spaces with grace and determination set her apart. She used her connections with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and other political figures to push for policies that directly benefited Black communities. Height believed in lifting as she climbed, mentoring young women who would continue the fight. She made sure that Black women weren’t just supporting the movement but leading it.

4. Shirley Chisholm Broke Political Barriers

Shirley Chisholm wasn’t just the first Black woman elected to Congress—she was a force of nature. When she won her seat in ‘68, she made it clear that she wasn’t there to be silent. Her slogan, “Unbought and Unbossed,” wasn’t just catchy—it was her truth. Chisholm refused to let party politics dictate her actions, advocating fiercely for the marginalized. She fought for education reform, knowing that access to quality schooling was a major barrier for Black children. She also pushed for better housing policies, recognizing that systemic racism kept Black families in substandard conditions.

As a congresswoman, she challenged the Democratic Party’s neglect of Black communities. She spoke out against the Vietnam War, calling it a waste of resources that should be spent on domestic issues. Chisholm also tackled gender inequality, demanding equal pay and protections for women in the workforce. She co-founded the National Women’s Political Caucus in ‘71, proving her commitment to intersectional activism. Though many tried to undermine her, she never let racism or sexism hold her back. By the time the ‘60s ended, she had already set the stage for a groundbreaking presidential run in ‘72. Chisholm proved that Black women had a rightful place in politics, paving the way for future generations.

5. Diane Nash Led the Charge for Nonviolent Resistance

Diane Nash wasn’t just a participant in the Civil Rights Movement—she was a leader, strategist, and fearless organizer. As a student at Fisk University, she became one of the driving forces behind the Nashville sit-ins of ‘60, which successfully desegregated lunch counters in the city. But she didn’t stop there. She co-founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and played a major role in organizing the Freedom Rides in ‘61. When the original riders were attacked in Alabama and the campaign seemed doomed, Nash refused to let violence win. She recruited a fresh group of riders and ensured the mission continued, knowing the risks involved. She was only in her early 20s, yet she was outsmarting segregationists and forcing the federal government to take action.

In ‘63, Nash moved her efforts to Selma, Alabama, where she worked on voting rights initiatives that would later influence the historic Selma marches. She believed in nonviolence not just as a tactic, but as a philosophy—one that demanded discipline, courage, and deep love for humanity. Even when she was arrested and pregnant, she refused to pay bail, choosing instead to serve time as a form of protest. Nash’s commitment to direct action made her one of the most effective leaders of the decade, though she rarely sought the spotlight. She challenged both racism and sexism within the movement, ensuring that women’s voices were heard. Her strategic mind and unwavering moral clarity shaped some of the most important victories of the ‘60s. Without Nash’s leadership, the Freedom Rides, sit-ins, and voting rights campaigns might not have had the same impact.

6. Ella Baker Built the Foundation for Grassroots Activism

Ella Baker was the kind of leader who didn’t need fame to make a difference—she believed in empowering others to take action. She had been working in the civil rights movement for decades before the ‘60s, but this was the decade where her influence became undeniable. As one of the founders of SNCC, she encouraged young activists to take control of their own movement rather than rely on traditional male-dominated leadership. She believed that real change came from the people, not from charismatic figures alone. Her philosophy of grassroots organizing laid the foundation for many of the decade’s biggest campaigns, from voter registration drives to direct-action protests.

Baker also played a crucial role in expanding the reach of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), though she often clashed with male leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. over their top-down approach. She believed in collective leadership and wasn’t afraid to challenge authority, even within her own movement. Throughout the ‘60s, she worked tirelessly to support local organizing efforts in the Deep South, ensuring that everyday people had the tools and knowledge to fight for their rights. Baker’s legacy isn’t just in the victories of the Civil Rights Movement—it’s in the leadership structures she helped create. She proved that activism wasn’t about fame or speeches but about empowering communities to fight for themselves.

7. Kathleen Cleaver Redefined Black Power and Women’s Roles in the Movement

Kathleen Cleaver wasn’t just the wife of a Black Panther leader—she was a revolutionary in her own right. As the first woman to hold a leadership position in the Black Panther Party, she shattered expectations about women’s roles in radical movements. She served as the party’s Communications Secretary, ensuring that their message reached the masses. Cleaver understood the power of imagery and rhetoric, helping shape the Panthers’ public presence. She was often seen speaking at rallies, challenging the media’s portrayal of the party as violent thugs rather than community organizers. Her speeches were sharp, passionate, and deeply rooted in the struggles of Black people.

Cleaver also worked to uplift Black women within the movement, arguing that gender equality had to be part of the fight for racial justice. She helped lead the Panthers’ community programs, including free breakfast initiatives and healthcare clinics, which directly served Black neighborhoods. In the late ‘60s, she went into exile with other Panther leaders but remained committed to the struggle. Cleaver’s presence in the movement was a direct challenge to the idea that Black Power was a male-dominated space. She proved that women were not just supporters but leaders, thinkers, and revolutionaries in their own right. Her work helped shape the image of the modern Black radical, making it clear that women were at the forefront of the fight.