1. Burning Herbs in the Streets

When plague swept through medieval towns, people often set piles of herbs and spices on fire right in the middle of the streets. The idea was that the sweet or pungent smoke would drive away the “bad air” thought to cause sickness. Rosemary, sage, and juniper were especially popular because they smelled strong and were believed to hold protective powers. It must have been a surreal sight, smoke filling narrow alleys where neighbors huddled, hoping the fumes would keep death at bay.

Of course, we now know this ritual did little to stop infection, but at the time it was considered essential. Entire communities participated, turning it into almost a public event. The choking clouds of smoke gave people a sense of control when so much else was uncertain. While not effective, it highlights just how desperately humans will cling to ritual when fear is everywhere.

2. Carrying Posies in Pockets

The old nursery rhyme “Ring Around the Rosie” hints at this practice. People literally carried small bouquets of flowers, called posies, in their pockets or around their necks. They believed the pleasant fragrance would protect them from the foul air thought to carry plague. In a world without real medicine, a handful of blooms was considered a kind of shield.

Doctors, nobles, and even children clutched flowers as they went about daily life. The bright colors and sweet scents brought comfort, even if they did nothing to stop disease. It’s oddly touching to imagine whole towns perfumed with blossoms, as if beauty itself could ward off death. In some ways, it was a ritual of hope as much as protection.

3. Flagellant Processions

In some parts of Europe, groups of men would march through towns whipping themselves with ropes or chains. They believed this act of penance would appease God and end the plague. Covered in blood and chanting prayers, they created a grim spectacle that terrified and fascinated onlookers. Communities sometimes joined in, thinking the ritual suffering might save them all.

The flagellants saw their pain as a holy offering, a way of begging for mercy. But the gatherings often spread the very disease they hoped to prevent. Authorities eventually banned the processions, fearing they caused more harm than good. Still, for those who took part, the ritual must have felt like their only hope in a time of despair.

4. Drinking Vinegar Mixtures

When medicine failed, people often turned to strange drinks. One common remedy was “Four Thieves Vinegar,” a mixture of vinegar infused with herbs like garlic, rosemary, and cloves. Legend has it that thieves who robbed plague victims without catching the disease credited their survival to this concoction. Soon, everyone wanted to sip or bathe in it.

The ritual of preparing and drinking these vinegars gave people a sense of taking action. They weren’t just waiting for the plague to strike, they were fortifying themselves with a kind of folk potion. The sour, pungent taste may have been unpleasant, but it carried with it the comfort of belief. In times of fear, even vinegar could become sacred.

5. Locking the Sick Away

Communities often resorted to locking the sick inside their homes, marking the doors with painted symbols or warning signs. This grim ritual was meant to contain disease, but it also isolated entire families. Neighbors would leave food at the doorstep but rarely dared to speak or make eye contact. It was both a protective measure and a chilling sentence.

For the healthy, this practice was reassurance that something was being done. For the sick, it was a lonely form of punishment that blurred the line between care and abandonment. The ritual of sealing doors with chalk or paint turned ordinary homes into silent tombs. It’s one of the darker ways fear reshaped daily life.

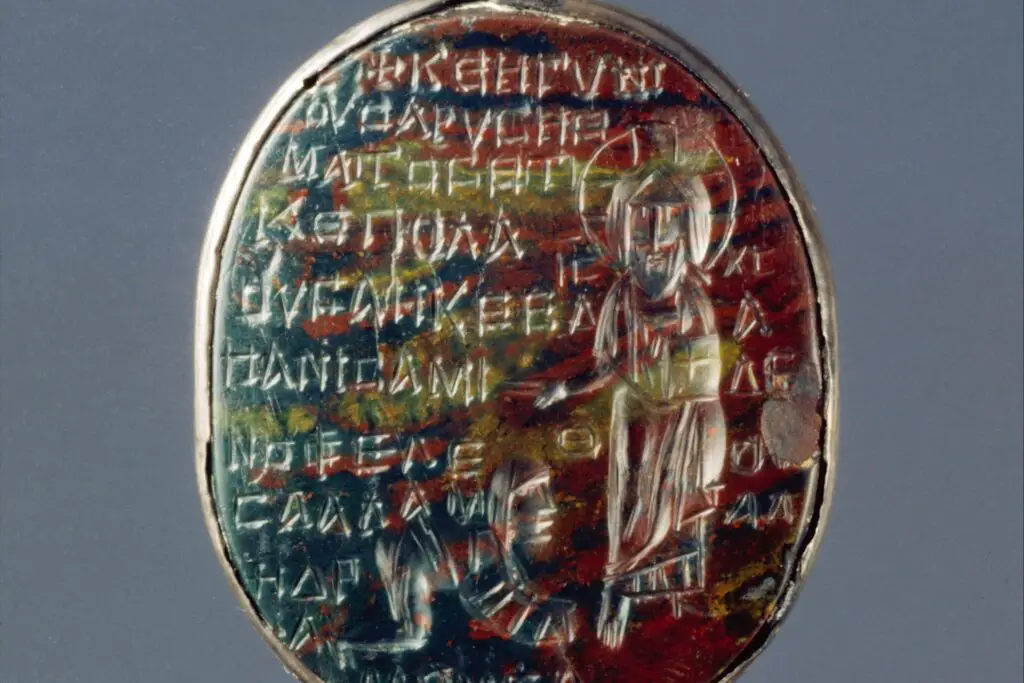

6. Wearing Amulets Against Evil

From carved crosses to small pouches filled with herbs or stones, amulets were everywhere during plague times. People believed disease was tied to evil spirits or curses, and these objects could ward them off. Children might wear a piece of coral around their necks, while adults clutched talismans engraved with holy words.

The act of wearing an amulet was deeply personal, a way to carry a sense of safety wherever you went. Families passed them down or crafted them by hand, imbuing them with love as much as superstition. They may not have worked medically, but the comfort they offered was real. In a way, they were tiny rituals carried right against the skin.

7. Burning Sulfur and Pitch

If herbs didn’t seem strong enough, people turned to harsher smells. Sulfur, tar, and pitch were tossed into fires to create thick, acrid smoke. The stench was overwhelming, but it was believed to drive away plague spirits and purify the air. Towns filled with this choking haze, turning the atmosphere both suffocating and eerie.

The ritual was often done at night, adding to its unsettling effect. Families huddled in smoky homes, convinced the foul odor was saving them. It’s easy to imagine how terrifying it must have been to breathe in that air, both a shield and a torment. In desperate times, even poisonously bad smells became part of survival.

8. Silent Midnight Prayers

Some communities gathered in complete silence at midnight, believing hushed collective prayer would confuse or frighten away evil forces. Whole towns stood together, lips moving soundlessly under the moonlight. The eerie quiet was broken only by the occasional sob or cough. It was ritual theater, blending faith and fear into a strange form of protection.

The idea was that silence itself had power, as if sound might attract danger. For many, the shared stillness was both comforting and unsettling. It gave a sense of unity in facing the unknown, even while heightening the eerie atmosphere of plague nights. This ritual turned prayer into something both spiritual and otherworldly.

9. Bloodletting for Balance

Physicians of the time often recommended bloodletting, believing disease came from imbalances in the body’s humors. Cutting veins or using leeches was seen as a way to drain out illness. The ritual was clinical but also symbolic, like releasing evil from the body. It left people weak and often worsened their condition, but it was trusted for centuries.

Patients might undergo repeated sessions, each one reinforcing the belief that action was being taken. Families sometimes watched anxiously as blood dripped into bowls, hoping it carried the sickness away. Though ineffective, the ritual reflected the human need to find order in chaos. It was a painful attempt to control the uncontrollable.

10. Dancing to Ward Off Death

In some places, people believed frenzied dancing could scare away the plague. Communities joined in mass dances, sometimes lasting for days. Known later as “dancing plagues,” these events combined superstition with desperation. People danced until they collapsed, convinced motion would keep death from catching them.

The ritual had a carnival-like atmosphere, with music, shouting, and exhaustion blending into something surreal. Outsiders might see madness, but participants saw it as life-affirming resistance. Dancing together gave them a strange sense of control, even as plague raged outside. It was joy and terror woven into one chaotic act.

11. Carrying Mercury Charms

Mercury, now known to be toxic, was once thought to have protective properties. People carried small vials or charms containing the metal, believing it repelled disease. Some even dabbed it on their skin in tiny amounts, thinking it created a shield. The ritual mixed alchemy with folk belief, a dangerous combination.

The shiny, liquid metal must have seemed magical, almost otherworldly. To hold it was to grasp something rare and powerful, and that sense of power was comforting in times of plague. Sadly, the practice often poisoned those who tried it. It’s a haunting reminder of how far people would go in their search for safety.

12. Burying Protective Charms in the Ground

In villages, people sometimes buried charms, written prayers, or even small animals at the edge of town. The ritual was meant to create a protective boundary, trapping the plague outside. These hidden offerings acted like invisible walls, both physical and spiritual. Families often kept the location secret, as if the magic would fail if revealed.

The act of digging, burying, and covering the earth gave a sense of finality, like sealing away danger. It turned the land itself into a participant in the fight against disease. Though ineffective, it shows how communities relied on shared ritual to make sense of catastrophe. The earth became both a protector and a witness to human fear.