1. Peacock Pie (Medieval England)

In the Middle Ages, peacock wasn’t just eaten for its flavor—it was a showstopper centerpiece. Cooks would roast the bird, then carefully re-dress it in its iridescent feathers so it appeared whole on the table, head and all. Sometimes the beak was gilded in gold leaf, and it was served with rich sauces made from wine, spices, and almonds. Guests didn’t just eat it; they admired it first.

From a modern perspective, the heavy roasting, fatty sauces, and lack of vegetables would raise red flags. The meat itself is lean, but the preparation was saturated with butter and cream. And the display, while impressive, meant the food often sat out for hours—something today’s food safety experts would cringe at.

2. Swan Roast (Tudor England)

A swan on the banquet table signaled pure royalty in Tudor times. The bird would be plucked, roasted, and basted in copious amounts of butter or lard, then served on a silver platter. Sometimes the skin was coated in saffron for color, and the head and neck were propped upright for drama. To finish it off, a rich gravy was poured over the top.

While swan is edible, modern dietitians would question the massive amounts of fat and salt used in preparation. Pair that with the tradition of pairing it with sweet fruit sauces and pastry crusts, and you’ve got a calorie bomb. It was less about health and more about making a visual statement of power and wealth.

3. Dormice in Honey (Ancient Rome)

The ancient Romans had a taste for delicacies that seem bizarre today, and honey-glazed dormice were among the most extravagant. These small rodents were fattened in special jars, stuffed with minced meat and herbs, then rolled in honey and poppy seeds before roasting. They were considered a rich man’s snack, often served as an appetizer.

From a modern nutritional standpoint, the combination of fatty stuffing and sugar coating was indulgence at its peak. There was nothing light or balanced about it. And while honey has health benefits in moderation, here it was more of a candy glaze than a drizzle.

4. Whale Blubber “Muktuk” (Historic Arctic Communities)

Muktuk, a traditional Inuit food, is made from the skin and blubber of whales—often bowhead. Served raw, frozen, or pickled, it was (and still is) an important source of vitamin C and omega-3 fatty acids in Arctic diets. Historically, large gatherings would feature thick slabs cut into bite-sized cubes.

While it’s nutrient-dense for survival in harsh climates, modern dietitians might raise an eyebrow at the extremely high fat content. A single serving is loaded with calories, and in feasting amounts, it could easily exceed daily fat recommendations. Still, for communities without access to fresh produce, it was a vital food source.

5. Foie Gras en Croûte (France, 18th Century)

Foie gras has long been a symbol of French luxury, and in the 1700s it was often baked in a buttery pastry crust. The rich, fatty duck or goose liver was seasoned with cognac and herbs, wrapped in puff pastry, and baked until golden. Served in thick slices, it was paired with sweet wine or fig compote.

From a dietary perspective, foie gras is almost pure fat. Add the buttery pastry and sweet accompaniments, and you’ve got a triple threat to modern heart health. It was the kind of dish where richness wasn’t a side note—it was the main event.

6. Roast Bear Meat (Imperial Russia)

For the Russian elite, serving bear meat was a statement of both hunting skill and opulence. The meat was slow-roasted or braised, often with wild berries, heavy cream, and mushrooms. It was a dense, dark meat, rich in flavor and fat, and portions were anything but small.

Today, the saturated fat content alone would make a dietitian frown. Add in the cream-based sauces and the sheer portion sizes, and it’s a recipe for a heavy, calorie-laden meal. It was meant to be hearty and luxurious, not light or health-conscious.

7. Sturgeon in Aspic (Russian Tsarist Era)

Sturgeon, prized for both its flesh and its caviar, was a favorite at imperial banquets. The fish would be poached, then set in a shimmering gelatin made from its own stock, flavored with herbs and wine. The presentation was ornate, sometimes molded into elaborate shapes.

Modern nutrition experts would note that while fish is generally healthy, the aspic preparation was loaded with salt and sometimes extra animal fat. And the sheer quantity served at these events meant overconsumption was the norm. This was indulgence in both texture and scale.

8. Turtle Soup (Gilded Age America)

In the late 19th century, green sea turtle soup was a delicacy at upscale restaurants like Delmonico’s. The meat was simmered for hours with sherry, butter, and spices, resulting in a rich, silky broth. Sometimes mock turtle soup, made with calf’s head, was served as a cheaper alternative—but the real thing was the ultimate luxury.

From a modern lens, this soup was high in cholesterol and sodium. Paired with multiple other rich courses in a single meal, it was far from balanced. It was more about exclusivity than nutrition.

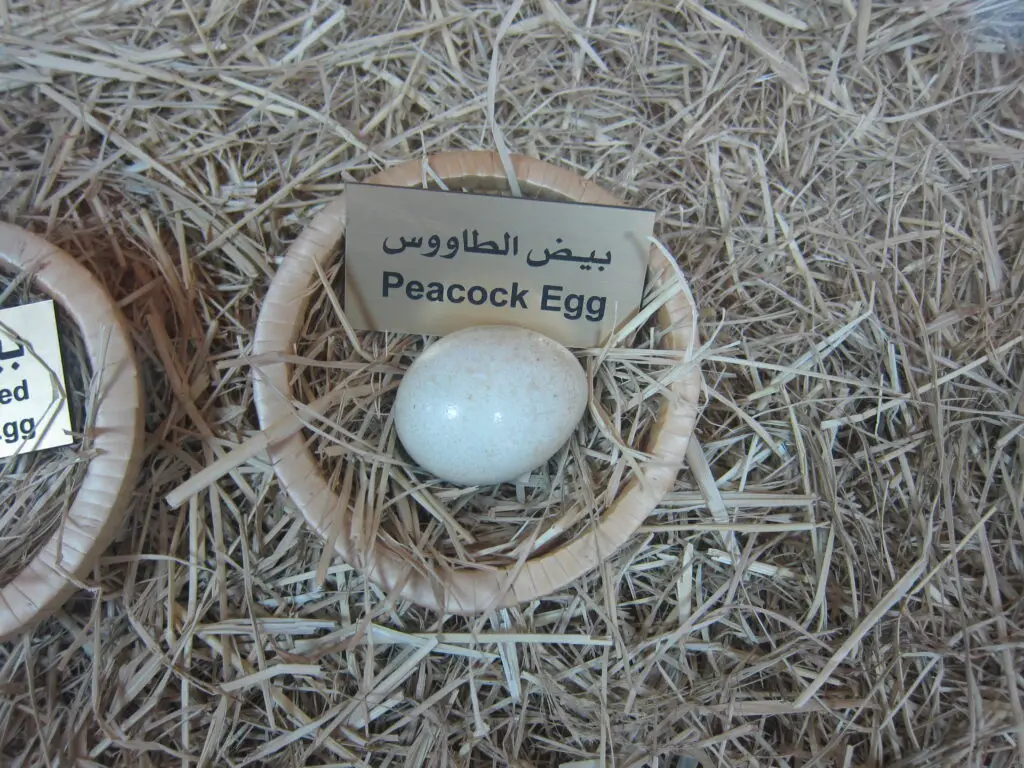

9. Stuffed Peacock Eggs (Medieval Banquets)

Peacock eggs, when available, were treated as precious rarities. They’d be hard-boiled, halved, and stuffed with a mix of ground meats, herbs, and spices, then baked again. The presentation often included elaborate trays and colorful garnishes.

While eggs themselves are healthy in moderation, these were far from simple boiled eggs. The meat-heavy stuffing and butter-rich baking made them calorie-dense, and portion sizes were generous. It was all about turning a rare ingredient into an even richer bite.

10. Baked Alaska (19th Century America)

When it debuted in the 1800s, Baked Alaska wowed diners with its theatrical flair. Layers of sponge cake and ice cream were covered in meringue, then quickly browned with a torch or in a hot oven. The contrast of hot exterior and frozen center made it a conversation piece.

Modern dietitians would see it as pure sugar and saturated fat. The dessert was enormous, often shared by the table, but in those days portion control wasn’t the goal. It was meant to be as indulgent as it looked.

11. Roast Boar’s Head (Medieval and Renaissance Europe)

The boar’s head was a centerpiece of grand winter feasts, often carried in on a platter with an apple in its mouth. The meat was roasted, basted in its own fat, and served with rich sauces made from wine and spices. It was considered a symbol of wealth and abundance.

Nutritionally, it was heavy, greasy, and sodium-laden. Combined with the lack of fresh greens on the table, it was a meat-lover’s dream but a health expert’s nightmare. It was meant to impress, not to nourish.

12. Baklava Towers (Ottoman Empire)

In the Ottoman court, baklava wasn’t just a dessert—it was an architectural feat. Layer upon layer of filo pastry, butter, and nuts was drenched in honey or sugar syrup, stacked into towering displays. Often, they were dusted with gold or studded with candied fruits.

The flavor was as rich as the appearance, but so was the calorie count. Packed with sugar and saturated fats from the butter, these pastries were anything but light. Yet for the sultans, sweetness was a sign of sophistication and hospitality.

13. Sugar Sculptures (Renaissance Italy and France)

Before chocolate became the dessert of choice, sugar was used to make intricate sculptures for noble tables. These creations could be shaped into castles, animals, or mythological scenes, painted with edible dyes, and sometimes even filled with candies. Guests would break pieces off to eat after admiring them.

The sculptures were pure sugar, with no nutritional value whatsoever. They were a marvel of craftsmanship but an overload of refined carbs. Modern dietitians would see them as art you probably shouldn’t eat.

14. Gilded Marzipan Fruits (16th–18th Century Europe)

Marzipan, a sweet almond paste, was molded into realistic fruit shapes, painted, and sometimes coated in gold leaf for royal tables. They were often used as edible decoration before being served as a sweet course. The flavor was nutty and rich, but the sugar content was sky-high.

While almonds offer healthy fats, the overwhelming ratio of sugar to nuts made them more candy than health food. And with gold leaf adding no nutrition, it was purely for show. Still, they remain one of the most photogenic indulgences from history.