The “Token Minority” Character

In the ’80s, it was almost guaranteed that any movie featuring a diverse cast would reduce non-white characters to shallow stereotypes. These characters were often written with no depth, existing solely to prop up the white protagonist. Whether it was the wise-cracking Black friend or the mystical Asian mentor, these roles were offensive and lazy. It sent a clear message that diversity wasn’t valued beyond being a backdrop for someone else’s story. Think of movies like Sixteen Candles, where Long Duk Dong’s portrayal was cringe-inducingly racist.

Audiences today demand more from filmmakers. Representation now means fleshed-out characters with their own arcs and agency, not caricatures meant for cheap laughs. It’s refreshing to see movies move away from these harmful tropes and toward authentic storytelling. But looking back, it’s astounding how many films fell into this trap. Movies like Breakfast at Tiffany’s set a terrible precedent that carried through the ’80s—thankfully, we’re leaving this one in the past.

Women as Damsels in Distress

In ’80s movies, women were often reduced to helpless victims waiting for a male hero to save them. Whether it was Princess Leia in Return of the Jedi being rescued by Luke and Han or Jennifer in Back to the Future, female characters rarely had autonomy. Their primary function was to look pretty, scream dramatically, and express gratitude once saved. It’s an outdated trope that aged badly.

Audiences have since grown tired of one-dimensional women. We now crave strong, capable female characters who drive their own narratives. Thankfully, modern films like Wonder Woman and Mad Max: Fury Road have set the bar higher. The ’80s’ portrayal of women as perpetual damsels has no place in today’s storytelling. Looking back, it’s hard not to cringe at how little agency these characters had.

“Nerds” as Punching Bags

The ’80s were a rough time for anyone portrayed as a nerd in movies. Films like Revenge of the Nerds reinforced the idea that geeks were socially inept losers who deserved ridicule. Often, these characters were relentlessly bullied, only gaining any semblance of respect after extreme measures like revenge or total personality overhauls. It was comedy at their expense, rooted in humiliating people who were different.

Now, nerd culture dominates pop culture. Shows like The Big Bang Theory prove that intelligence and quirkiness can be celebrated rather than mocked. The ’80s obsession with humiliating nerds feels mean-spirited and out of touch today. Instead of using nerds as the butt of every joke, modern stories celebrate their uniqueness and depth. The transformation is one we’re all better off for.

The “Deadbeat Dad” Redemption Arc

The trope of the absentee father showing up just in time to save the day was a staple of ’80s family dramas. Films like Kramer vs. Kramer or Over the Top loved to present fathers as initially neglectful but capable of miraculous redemption with a single grand gesture. Meanwhile, mothers often bore the brunt of the actual parenting without fanfare. The dad’s redemption was somehow supposed to erase years of neglect.

This tired storyline ignored the emotional complexities of parenting and the impact of neglect. Modern audiences expect more nuanced portrayals of family dynamics. Movies like Marriage Story show that relationships are complicated and can’t be fixed with clichéd heroics. The ’80s obsession with making deadbeat dads look heroic has thankfully been retired.

Endless Makeover Montages

Ah, the makeover montage—a hallmark of ’80s teen movies like The Breakfast Club and Pretty in Pink. These scenes often reinforced the idea that someone’s worth was tied to their appearance. Geeky girls like Allison in The Breakfast Club underwent drastic physical transformations, shedding their individuality to become more socially acceptable.

While these scenes were often fun, they sent harmful messages about beauty and self-worth. The implication was clear: you’re only lovable if you conform to societal standards. Today, we’re seeing a push for stories that celebrate authenticity and inner beauty. The ’80s obsession with superficial makeovers feels outdated and shallow in hindsight.

Villains Without Motivation

In the ’80s, villains were often evil just for the sake of being evil. Think of Skeletor in Masters of the Universe or the various cartoonish antagonists in action films. These characters had little depth, existing only to make the hero look good. While this approach worked for popcorn entertainment, it made these films forgettable.

Modern audiences demand more complex antagonists with understandable motivations. Movies like Black Panther and The Dark Knight have set a new standard for nuanced villains. Looking back, the ’80s’ cardboard-cutout bad guys feel lazy and uninspired. A well-written antagonist elevates the story, something many ’80s movies failed to achieve.

Overuse of the “Training Montage”

Few tropes scream ’80s quite like the training montage. From Rocky IV to The Karate Kid, these sequences were a staple of action and sports films. They usually involved an underdog hero sweating through an intense workout while inspirational music played. While undeniably fun, they’ve become a parody of themselves over time.

The problem with training montages is their reliance on shortcuts. They condense complex character development into a flashy music video. Modern audiences prefer to see gradual progress and deeper storytelling. The ’80s obsession with montages feels overly simplistic today, though we’ll admit they were catchy.

The “Cool” Bully

’80s movies often glorified bullies, portraying them as the epitome of cool. Characters like Biff Tannen in Back to the Future or Johnny Lawrence in The Karate Kid were depicted as charismatic but cruel. These bullies were rarely given consequences for their actions, reinforcing toxic behaviors.

Today, storytelling emphasizes accountability and emotional depth. Shows like Cobra Kai have revisited these characters, exploring their vulnerabilities and motivations. The glorification of bullies as aspirational figures feels tone-deaf in retrospect. Thankfully, this trope has been reexamined and largely retired.

The “Chosen One” Hero

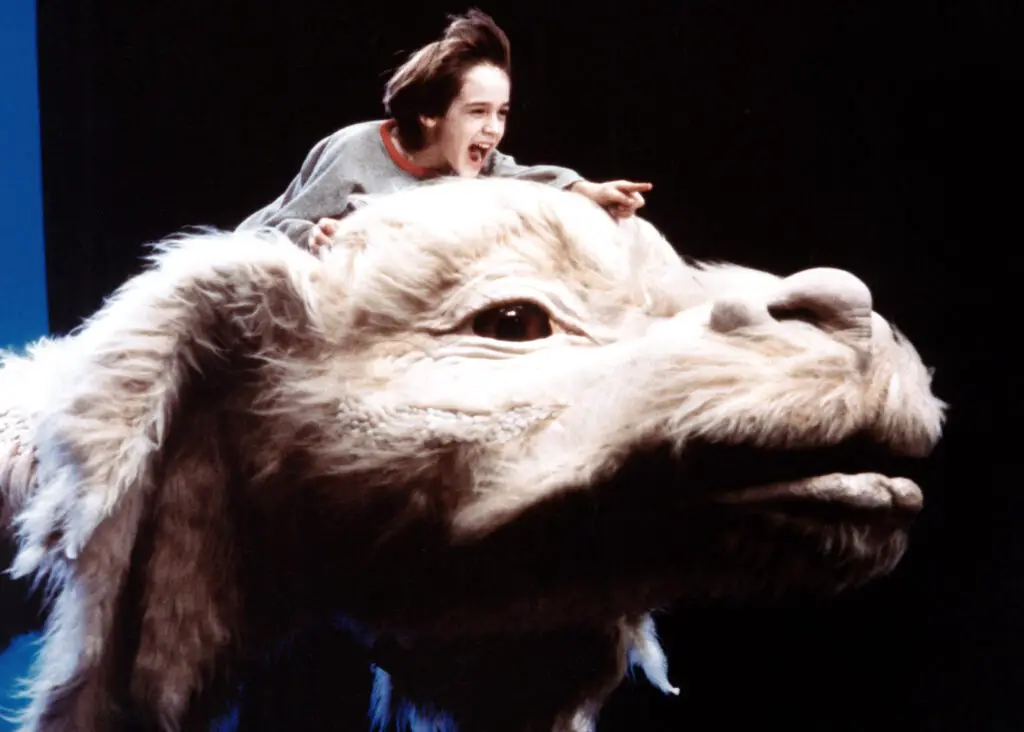

The ’80s loved stories about ordinary people suddenly discovering they were destined for greatness. Whether it was Luke Skywalker in Star Wars or Atreyu in The NeverEnding Story, this trope was everywhere. While fun, it often robbed characters of real growth by attributing their success to fate rather than effort.

Modern audiences favor more grounded heroes who earn their victories. Movies like Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse show that anyone can rise to the occasion without being “chosen.” The ’80s reliance on predestined heroes feels outdated, prioritizing spectacle over substance. It’s a trope we’re happy to leave behind.

Pointless Love Triangles

Romantic subplots in ’80s movies often relied on clichéd love triangles. Films like Pretty in Pink and Some Kind of Wonderful pitted characters against each other in contrived dramas. These subplots rarely added depth, existing only to create artificial tension.

Modern romances focus more on meaningful connections and authentic storytelling. The ’80s obsession with love triangles feels forced and unnecessary now. Audiences crave narratives that prioritize emotional resonance over cheap drama. Thankfully, this trope has mostly fallen out of favor.

The “Wise Old Mentor”

The ’80s were full of wise old mentors who existed solely to guide the hero. Think of Mr. Miyagi in The Karate Kid or Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back. While beloved, these characters often lacked their own arcs, serving as plot devices rather than fully realized people.

Today, mentorship is portrayed with more nuance. Films like Creed show mentors with their own struggles and growth. The ’80s tendency to reduce these characters to stereotypes feels limiting in hindsight. We’re now seeing richer, more dynamic portrayals that add depth to stories.

“Happily Ever After” Endings

In the ’80s, movies often wrapped up with overly simplistic happy endings. Whether it was the hero getting the girl or the villain being vanquished, these conclusions tied everything up with a neat bow. While satisfying, they often ignored unresolved issues or deeper complexities.

Modern films embrace ambiguity and open-ended storytelling. Movies like Inception and La La Land challenge audiences with endings that feel authentic rather than contrived. The ’80s obsession with perfect conclusions now feels dated and unrealistic. Life is messy, and stories should reflect that.

Over-the-Top Action Sequences

The ’80s were the golden age of gratuitous action scenes. Films like Rambo: First Blood Part II and Commando prioritized explosions and body counts over plot or character development. While entertaining, these sequences often felt excessive and devoid of substance.

Modern action films balance spectacle with storytelling. Movies like Mad Max: Fury Road prove that action can serve the narrative rather than overshadow it. The ’80s’ obsession with over-the-top sequences feels indulgent and shallow by today’s standards. We’re glad filmmakers have found a better balance.

Teenagers Played by Adults

In ’80s movies, it was common for actors in their late twenties to play high school students. Films like Grease and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off cast visibly older actors in teenage roles, creating a jarring disconnect. This trend often led to unrealistic portrayals of adolescence.

Today, casting younger actors brings more authenticity to teen dramas. Shows like Euphoria feature age-appropriate performers who better capture the complexities of youth. The ’80s’ reliance on adult actors for teen roles feels out of touch now. Authentic casting has made storytelling much more relatable.

The “Perfect” Nuclear Family

The ’80s idealized the nuclear family, portraying it as the pinnacle of happiness. Shows like Family Ties and movies like E.T. reinforced this trope, often sidelining alternative family dynamics. This narrow portrayal excluded diverse experiences and realities.

Modern stories embrace all kinds of families, from single parents to chosen families. Films like The Farewell and The Kids Are All Right highlight the beauty in non-traditional arrangements. The ’80s’ obsession with the perfect nuclear family now feels restrictive and outdated. Representation has thankfully expanded to reflect real-world diversity.

Sources: Vox, Screen Rant, Collider