1. Etruscan

Long before the rise of the Roman Empire, the Etruscans ruled central Italy and had a language all their own. While their civilization left behind beautiful art and elaborate tombs, their written words remain mostly a mystery. We’ve uncovered inscriptions on pottery, mirrors, and tomb walls, but the vocabulary and grammar are still only partially understood. What we do know comes mainly from short texts and a few bilingual translations, like one on a mummy wrapping reused from an Etruscan book according to GreekReporter.com.

It’s wild to think that this language once held sway over what would later become the heart of Western civilization. Imagine entire cities conversing in a tongue we can barely decipher today. The Romans eventually absorbed the Etruscans, and Latin became the dominant language. But echoes of Etruscan might still live on in some Roman religious rituals and customs that the Romans adopted without fully understanding shares Smithsonian Magazine.

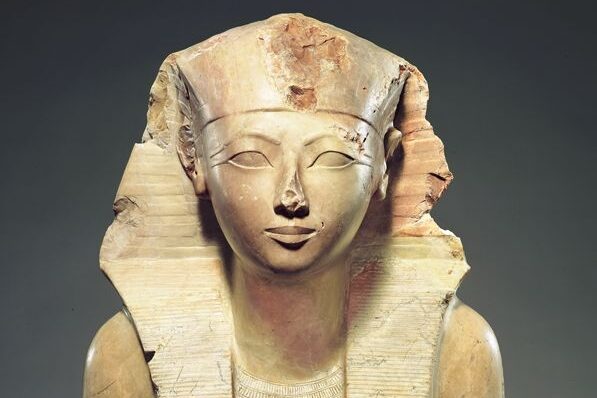

2. Coptic

Coptic is the final stage of the ancient Egyptian language, and it once served as the heart of Egypt’s Christian tradition. Written in the Greek alphabet with a few extra letters thrown in, Coptic flourished between the second and thirteenth centuries. At its peak, it wasn’t just a language, it was a connection to Egypt’s deep past and vibrant Christian faith. Churches, monasteries, and everyday Egyptians once relied on Coptic to record their prayers, letters, and ideas says Yale News.

Over time, Arabic slowly replaced Coptic in daily life, especially after the Muslim conquest of Egypt in the 7th century. But even though it faded from public use, it never truly disappeared. Today, Coptic still lives on in the liturgies of the Coptic Orthodox Church. So while it’s no longer spoken in homes or markets, its spiritual legacy carries on every time a hymn is sung adds the Conversation.

3. Gothic

Gothic might sound like it belongs in a Tim Burton film, but it was once the spoken word of entire Germanic tribes, including the Visigoths and Ostrogoths. It’s also the oldest Germanic language we have in a relatively complete form, thanks to a bishop named Ulfilas who translated the Bible into Gothic in the 4th century. He even invented a special alphabet to do it, which is pretty impressive when you think about it. That version of the Bible became a rare treasure that helps us glimpse into a vanished world.

Gothic eventually vanished as the tribes that spoke it were absorbed into other cultures across Europe. It didn’t evolve like English or German, it just… stopped being spoken. Some of the last records of Gothic being used date to the 9th century. It’s a little sad to think of a language with such a dramatic name and rich heritage going quiet so early.

4. Sogdian

If you traveled along the Silk Road centuries ago, chances are you’d run into someone speaking Sogdian. It was the lingua franca of traders and merchants crossing Central Asia, connecting cultures from China to Byzantium. The Sogdians left behind colorful letters, contracts, and religious texts, some of which date back to the 4th century. Their language borrowed and shared freely, soaking up influences like a sponge.

But over time, Sogdian was replaced by Persian and other Turkic languages as trade routes shifted and empires changed hands. The decline wasn’t sudden, just a slow fade into history. Still, traces of it live on in modern-day Yaghnobi, a language spoken by a small community in Tajikistan. It’s like a tiny ember glowing where a roaring fire once blazed.

5. Hittite

The Hittites were a major power in the ancient world, and their language—Hittite—was once the dominant tongue of what is now Turkey. It’s the oldest known Indo-European language, which makes it a linguistic ancestor of English, Spanish, and Hindi. For centuries, it lay hidden on clay tablets, written in cuneiform, and mistaken for something else entirely. Only in the 20th century did scholars crack the code and realize they had stumbled onto something huge.

These tablets recorded treaties, prayers, laws, and myths, giving us a peek into a civilization that rivaled Egypt and Babylon. But the Hittite Empire collapsed around 1200 BCE, part of the larger Bronze Age downfall. Without an empire to support it, the language vanished within a few generations. Now, it survives only in museums and the occasional college linguistics course.

6. Ainu

The Ainu people of northern Japan and parts of Russia once spoke a language that was completely unique—unrelated to Japanese, Korean, or any other known language. Ainu was passed down orally, through stories, chants, and rituals, giving it a deeply spiritual character. It was never widely written, which made it even more vulnerable as Japanese became dominant. Over time, the number of speakers dwindled to just a handful.

Today, Ainu is considered critically endangered, but not completely lost. Cultural revival efforts are underway, with language classes and storytelling events aimed at preserving this special part of Japan’s heritage. Still, it’s heartbreaking to think how close we came to losing it completely. Ainu offers a glimpse into a worldview shaped by nature, tradition, and resilience.

7. Tocharian

Imagine a European language spoken in western China—that’s Tocharian. It was used by Buddhist monks and travelers along the Silk Road, and its discovery in the early 20th century surprised everyone. It looked Indo-European, but it was found in a place no one expected. Manuscripts written on palm leaves and wall murals preserved bits of the language, giving scholars a real puzzle to solve.

Tocharian came in two distinct varieties, Tocharian A and B, used between the 6th and 9th centuries. Eventually, the spread of Turkic and Chinese languages pushed it out. It disappeared quietly, its speakers absorbed into the larger cultural tide. Today, Tocharian is a linguistic ghost, fascinating in its journey and mysterious in its silence.

8. Manx

Manx hails from the Isle of Man, tucked between Ireland and England, and is a Gaelic language with a plucky attitude. For centuries, it was the heart and soul of island life, spoken in homes, pubs, and churches. But like many minority languages, it faced stiff competition from English, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries. By the 1970s, it was declared extinct as a native language.

But here’s the twist—Manx didn’t stay extinct. A cultural revival began in the late 20th century, with schools teaching it and children growing up bilingual. Now, you can even hear it on the radio or see it on street signs. It’s a beautiful example of how a “lost” language can make a comeback with enough heart and community support.

9. Old Prussian

Before the rise of modern Germany and Poland, there were the Prussians—and they spoke a Baltic language called Old Prussian. It was closer to Lithuanian and Latvian than to German, and it held its own for centuries. Unfortunately, the Teutonic Knights and later Germanic influence pushed it out. By the 18th century, the last native speakers had died out.

Old Prussian left behind a handful of religious texts, vocabulary lists, and place names. It’s enough for linguists to piece together its structure, but not enough to revive it as a living language. Still, there are enthusiasts today trying to bring it back through reconstructions and educational efforts. It’s a quiet tribute to a people and culture long absorbed by history.

10. Elamite

Elamite was spoken in what is now southwestern Iran and dates back over 3,000 years. It was the official language of the Elamite Empire, which rubbed shoulders with Babylon and Assyria. Unlike its neighbors, Elamite didn’t belong to any known language family, making it a bit of a loner in the ancient world. It used cuneiform script and was written on thousands of tablets.

The language stuck around through various phases, even after the Elamite Empire fell. Eventually, it gave way to Old Persian and other regional dialects. Scholars are still debating its origins and structure, which makes every Elamite inscription a bit of a mystery. It’s one of those languages that reminds us just how much we still don’t know.

11. Punic

Punic was the language of Carthage, the North African city that gave Rome such a run for its money during the Punic Wars. It was a later form of Phoenician, brought westward by seafaring traders and conquerors. At its height, Punic was spoken across parts of North Africa, Spain, and the Mediterranean islands. It was a powerful language tied to a powerful rival of Rome.

Even after Carthage was destroyed, Punic held on in some regions for centuries. Saint Augustine even mentioned that Punic was still spoken in his time, in the 5th century CE. But slowly, Latin and later Arabic took over, and Punic faded into obscurity. Today, we mostly know it from inscriptions and the occasional Roman mention.

12. Tangut

Tangut was the language of the Western Xia dynasty, which ruled parts of northwestern China between the 11th and 13th centuries. Its writing system was notoriously complex, with tens of thousands of characters. The Tangut people were powerful, well-organized, and left behind a rich cultural legacy. But their language didn’t survive the Mongol invasion.

For centuries, Tangut remained an enigma until scholars finally began deciphering its script in the 20th century. It’s now considered a linguistic isolate, with no known relatives. The surviving texts, mostly Buddhist scriptures, offer a rare look into a vanished world. Tangut is a reminder of how easily entire cultures can be wiped from memory.

13. Meroitic

In the shadow of ancient Egypt, the Kingdom of Meroë thrived along the Nile in what is now Sudan. Their language, Meroitic, was written in its own unique script and used in official inscriptions, tombs, and monuments. Despite plenty of surviving examples, we still haven’t cracked the code completely. Meroitic remains one of the great unsolved puzzles in linguistics.

It fell out of use around the 4th century when the kingdom declined and other languages took over. Scholars have been trying to decode it for over a hundred years, with only partial success. We know how to read the alphabet, but we don’t know what most of the words mean. It’s like having the pieces to a beautiful mosaic but no idea what picture they make.