1. The Flat Earth Theory

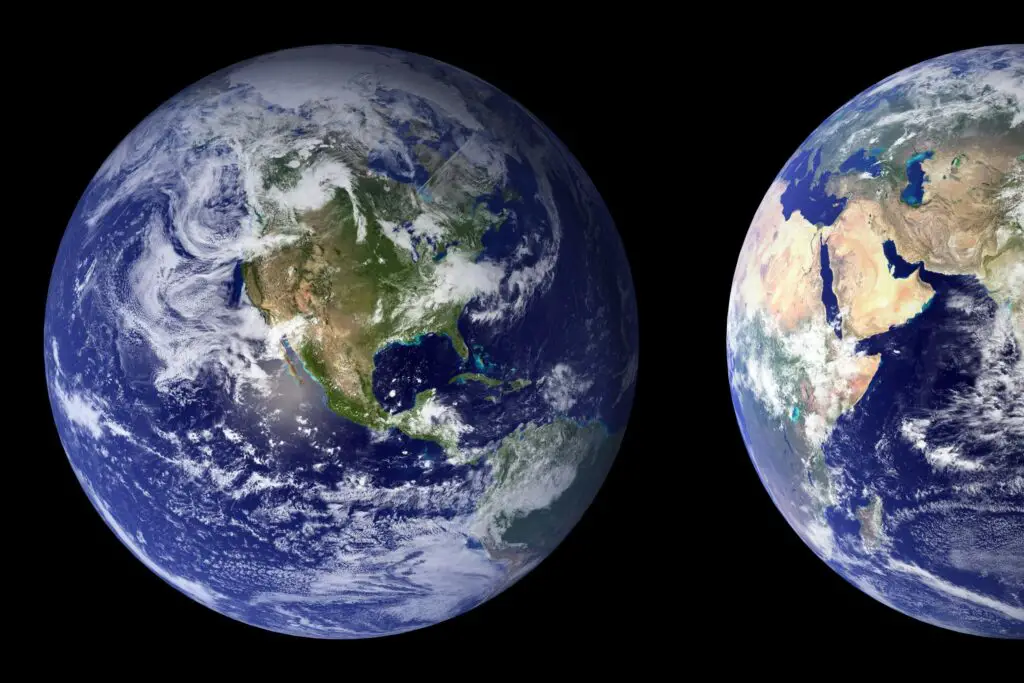

For a surprising stretch of early American education, the idea that Earth was flat wasn’t just a fringe belief, it was taught in classrooms as established fact. In the 1800s, schoolbooks in certain regions treated this concept as common knowledge, even though science had already proven the planet’s roundness centuries earlier. Many teachers passed this on without question, relying on outdated texts or their own limited training. It sounds wild now, but geography lessons often described the Earth as a flat plane, with the sun rising and setting across its surface shares NASA.gov.

Part of the reason it lingered was religious interpretation and a deep mistrust of newer scientific thought. For kids growing up in small towns, especially in isolated communities, this version of reality was never challenged. They weren’t taught about gravity, satellites, or circumnavigation, just a simple map and a flat world. It wasn’t until better teacher education and updated textbooks rolled out that this myth finally stopped being treated like science adds USA Today.

2. Spontaneous Generation

Imagine being told that flies came from meat and mice came from piles of grain. That was the logic behind spontaneous generation, a belief that living organisms could appear out of nonliving matter. For centuries, including in U.S. schools through the 1800s, this was taught as a valid explanation for life’s origins. Science classes sometimes used rotting meat in a jar as a demonstration, claiming the maggots proved life could just appear says Wikipedia.

It wasn’t until the experiments of Louis Pasteur in the mid-1800s that this myth was officially debunked. But even then, it took time for the findings to reach classrooms and reshape the science curriculum. Older teachers and textbooks continued spreading the outdated belief for decades. So, students were memorizing a “fact” that was already known to be false in the scientific world shares Britannica.

3. The Four Humors

If you were a student in the early 19th century learning about health, chances are your teacher mentioned the four humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. This theory, passed down from ancient Greece, claimed that your physical and mental health depended on keeping these in balance. It wasn’t just folklore, it was the backbone of early medical instruction in many American schools.

Some schools even taught that personality traits were caused by having too much of one humor, like being too angry due to excess yellow bile. It sounds like a wild horoscope, but it shaped how illnesses were treated for centuries. Leeching and “bleeding” patients to balance humors were lessons included in early biology and health classes. It took major advances in biology and medicine before this pseudoscience finally got replaced.

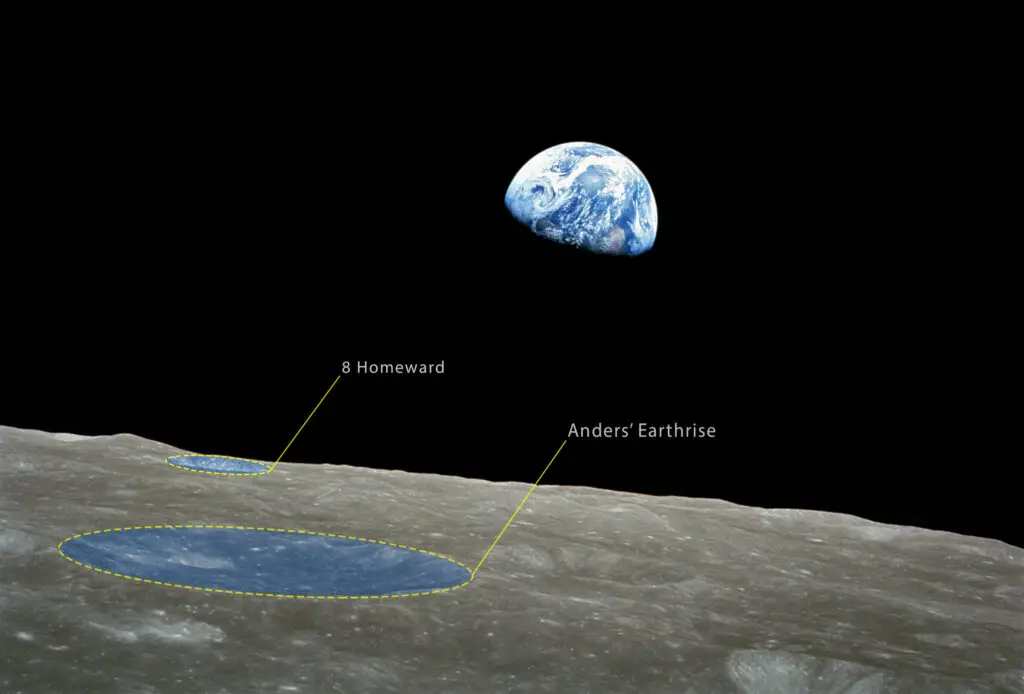

4. Geocentrism

For a long time, students learned that Earth was the center of the universe, with the sun and planets revolving around it. This ancient belief, rooted in Ptolemaic astronomy, made its way into early U.S. classrooms through outdated religious and scientific texts. Even though Copernicus and Galileo had disproved this idea centuries earlier, American textbooks clung to it well into the 1800s.

Many early teachers simply didn’t know any better and taught what they’d learned themselves. The concept of heliocentrism, with the sun at the center, took time to gain trust in conservative educational circles. Some communities resisted it, thinking it contradicted scripture. So for years, American kids learned a model of the cosmos that was more medieval than modern.

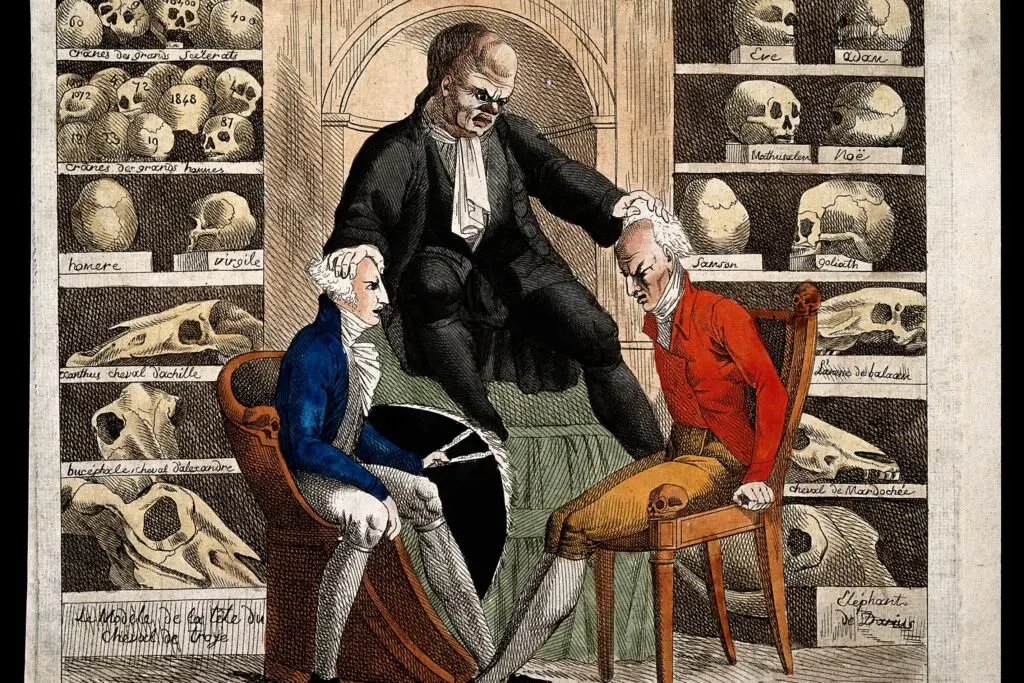

5. Phrenology

Phrenology was once considered cutting-edge science, and yes, it was taught in American schools. This was the belief that you could determine a person’s character, intelligence, or morality based on the shape of their skull. Teachers would point to diagrams of the head with labeled “faculties” and explain how bumps and dents revealed personality traits.

It gained major traction in the 19th century and even made its way into early psychology courses. Unfortunately, it also supported racist and classist ideas, justifying discrimination under the guise of science. Despite being completely debunked by the late 1800s, phrenology hung on in some classrooms into the early 1900s. It’s one of those myths that sounds absurd now but once passed as serious education.

6. Bleeding as a Cure-All

In early American classrooms, students learned that “bad blood” was to blame for illness. The go-to solution? Bleeding. Health and science lessons promoted this as a legitimate treatment, even long after it had been disproven in Europe. Kids were taught about leeches, lancets, and the belief that draining blood could restore balance in the body.

It wasn’t limited to old-timey barber-surgeons either, it was part of classroom instruction on how the body worked. Even George Washington’s death was taught with a shrug, saying he’d just needed more bleeding. The irony is, this harmful practice often made people worse. It took generations and better medical understanding before the idea was fully removed from schools.

7. Racial “Science”

One of the most harmful myths taught as science was the idea that different races belonged to distinct biological “types,” with white people considered superior. These theories were often packaged in anthropology or biology classes in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Students were shown charts ranking skull sizes or intelligence by race, all completely fabricated.

This was junk science used to justify slavery, segregation, and discrimination. What’s worse is that respected schools and institutions backed it, giving it the appearance of legitimacy. It wasn’t just a footnote in history—it shaped how entire generations understood race. Thankfully, modern science and civil rights movements dismantled this ideology, but its damage lasted long after it left the classroom.

8. The Miasma Theory

Before germ theory was widely accepted, kids learned that diseases came from “bad air,” or miasma. Teachers explained that clouds of stinky, rotting air could make you sick, and cities even tried to control illness by fighting smells instead of microbes. Students might have believed that cholera came from the odor of garbage or that malaria floated in on a breeze.

This theory stuck around because it felt logical—people really did get sick near swamps or in filthy conditions. But without understanding germs or bacteria, teachers had no better explanation. It took pioneers like John Snow and later Louis Pasteur to replace miasma with germ theory. Until then, students were being taught to fear air, not the invisible bugs it carried.

9. Earth Is Only 6,000 Years Old

For a long time, especially in religious schools, kids were taught that Earth was just a few thousand years old. This belief came from calculating Biblical timelines, particularly from Bishop Ussher, who said Earth was created in 4004 BC. It was treated as fact in many science classrooms before geology and paleontology took hold.

Even as fossils and carbon dating suggested a much older Earth, some schools resisted updating their lessons. Textbooks in certain areas clung to young-Earth creationism into the mid-1900s. It became a flashpoint for the science vs. religion debate that still lingers today. But for many kids, their first “scientific” understanding of Earth’s age was closer to Sunday school than the Smithsonian.

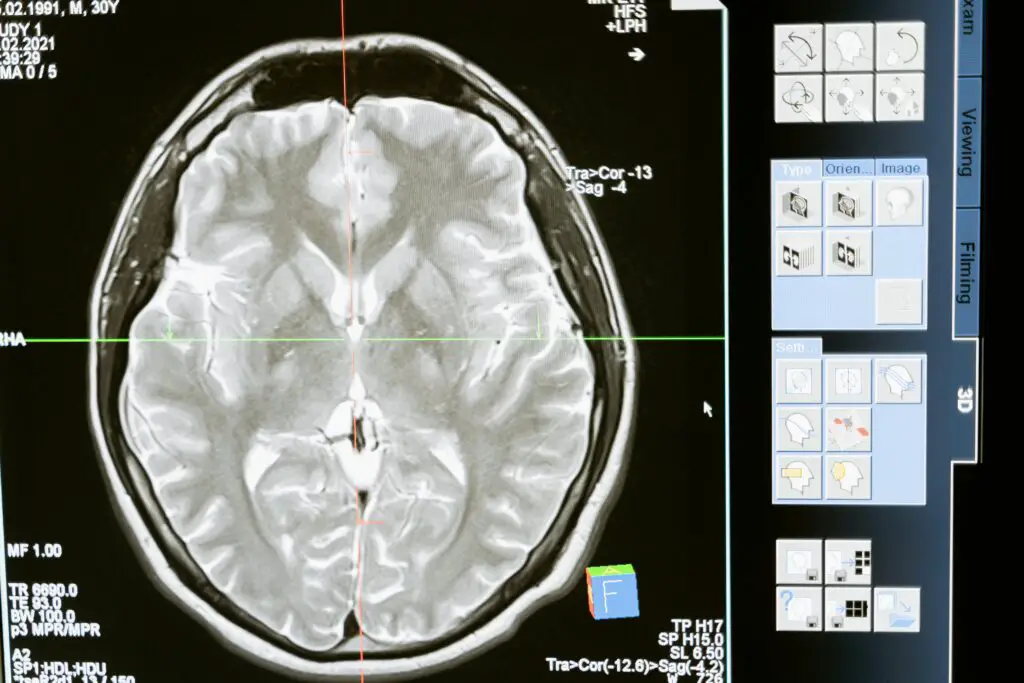

10. Humans Only Use 10% of Their Brains

This myth still sneaks into pop culture today, but it was once taught in psychology and science classes as if it were solid truth. The idea was that 90% of our brain just sat there, unused, waiting to be unlocked. Students were encouraged to believe in hidden potential and miracle abilities.

While well-meaning, this “fact” had no basis in actual neuroscience. Teachers repeated it without question, and it made its way into textbooks and motivational speeches. In reality, we use virtually every part of our brain throughout the day. The 10% myth may sound inspiring, but it kept generations from understanding how their brains really work.

11. Dinosaurs and Humans Coexisted

In certain schools, especially those with religious leanings, kids were taught that humans and dinosaurs lived at the same time. Textbooks and lectures explained that fossils showed they walked the Earth together, sometimes even claiming humans rode dinosaurs. It was a blend of Biblical interpretation and wishful thinking disguised as science.

This teaching contradicted everything paleontology had uncovered, yet it persisted well into the 20th century. Some children were shown illustrations of dinosaurs pulling carts or mingling with early humans. These lessons weren’t based on fossil records but on literal readings of religious texts. For students in these classrooms, science and scripture were one and the same.

12. The Inheritance of Acquired Traits

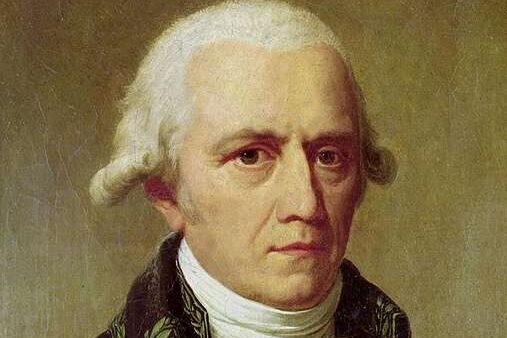

Based on the outdated ideas of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, students were once taught that traits developed during an organism’s life could be passed to its offspring. For example, if a giraffe stretched its neck to reach tall trees, its babies would be born with longer necks. Early biology lessons used this as a cornerstone before Darwin’s theory of evolution gained ground.

The idea stuck because it was easy to grasp and sounded reasonable. Teachers liked it for its simplicity, and it lingered in textbooks even after it had been disproven. It took time for natural selection and genetics to be fully understood and replace Lamarckian thinking. Until then, American students learned a version of evolution that nature simply doesn’t support.