1. Judas Iscariot Might Have Been Following Orders

Judas Iscariot is one of the most infamous traitors in history, remembered for betraying Jesus for 30 pieces of silver. But some scholars argue that Judas may have simply been doing what Jesus wanted all along. The Gospel of Judas, an ancient text discovered in the 1970s, suggests that Jesus himself asked Judas to turn him in. This would mean that instead of being a villain, Judas was actually the most loyal disciple, carrying out a painful but necessary role. After all, without the betrayal, the crucifixion and resurrection wouldn’t have happened as they did shares the Collider.

There’s also the possibility that Judas was more of a scapegoat than a true villain. The gospels were written long after the events took place, and each one tells a slightly different version of the story. Some early Christian groups even revered Judas for his role in fulfilling prophecy. It’s also worth noting that the name “Judas” became heavily associated with betrayal after the fact, making it hard to separate the man from the myth. Whether he was a traitor or simply misunderstood, his story is far more complicated than it seems adds PEOPLE.

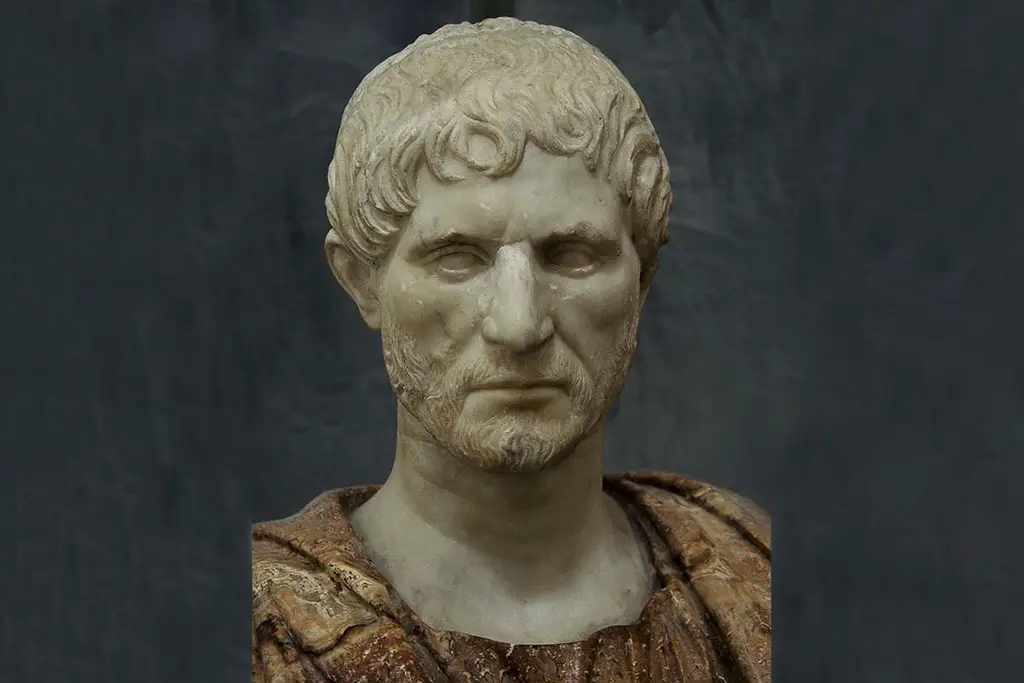

2. Brutus Might Have Saved the Roman Republic

Marcus Junius Brutus is best known as the man who helped assassinate Julius Caesar, an act that has gone down in history as the ultimate betrayal. But from his perspective, he wasn’t backstabbing a friend—he was trying to stop a dictator. Rome was a republic, but Caesar was consolidating power in a way that looked a lot like a monarchy. Brutus and his fellow senators feared that if they didn’t act, Rome would never be free again. Killing Caesar was a desperate attempt to preserve democracy shares Wikipedia.

Unfortunately, things didn’t go as planned. Instead of restoring the republic, Caesar’s assassination led to a brutal civil war that ended with his adopted heir, Octavian, becoming Rome’s first emperor. In hindsight, it’s easy to say Brutus failed, but his intentions were noble. He believed he was protecting Rome from tyranny, not just playing politics. His legacy as a traitor overshadows the fact that he was trying to prevent exactly the kind of empire that Rome ultimately became.

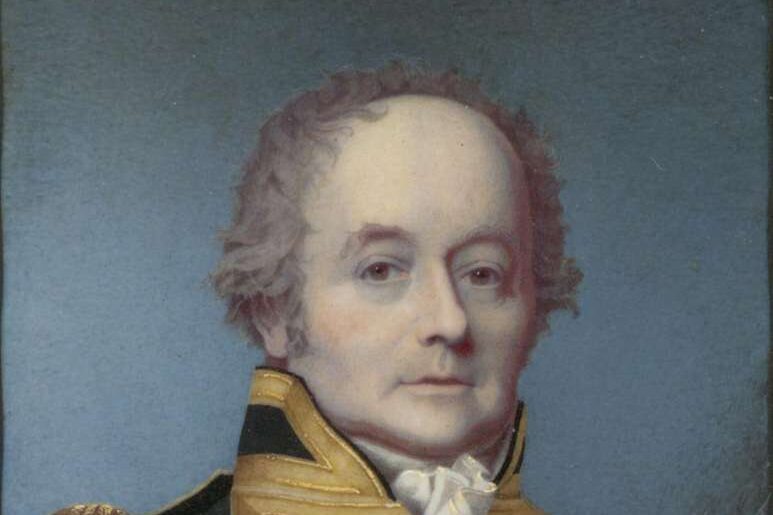

3. Captain William Bligh Wasn’t the Tyrant We Thought

Captain William Bligh is often portrayed as a cruel and incompetent leader, thanks in large part to Mutiny on the Bounty. But the real story is much more complicated. While Bligh was strict, there’s little historical evidence that he was unusually harsh for his time. His crew mutinied because they had spent months in the paradise of Tahiti and didn’t want to go back to the brutal life at sea. Bligh’s real crime may have been trying to do his job too well adds Britannica.

After being set adrift in a tiny boat with loyal crew members, Bligh navigated over 3,600 miles to safety—an incredible feat of seamanship. Later in life, he continued to serve in the Royal Navy and was even promoted. The image of him as a tyrant mostly comes from the exaggerated accounts of the mutineers, who needed to justify their rebellion. In reality, he was a capable officer who just had the bad luck of dealing with sailors who wanted an extended vacation.

4. Richard III Might Not Have Killed the Princes

Richard III has been painted as one of England’s greatest villains, accused of murdering his young nephews to seize the throne. Shakespeare’s Richard III cemented his reputation as a hunchbacked schemer. But there’s no concrete proof that Richard was responsible for the deaths of the “Princes in the Tower.” The boys disappeared, but their fate remains a mystery. Some historians believe they were killed by Henry VII, who had just as much motive.

Richard’s short reign was actually fairly progressive. He passed laws that improved the justice system and helped the common people. His portrayal as a monstrous usurper mostly comes from Tudor propaganda, written after he was defeated by Henry VII. The discovery of his skeleton in 2012 even disproved some of the rumors about his appearance. He may not have been a saint, but he probably wasn’t the villain history makes him out to be.

5. Marie Antoinette Didn’t Actually Say “Let Them Eat Cake”

Marie Antoinette is often blamed for the downfall of the French monarchy, accused of being out of touch and heartless. The famous quote, “Let them eat cake,” is often cited as proof of her indifference to the starving poor. But there’s no evidence she ever said it—it was actually attributed to an unnamed noblewoman years before she even became queen. The real Marie Antoinette was more complex than her reputation suggests.

While she did live a lavish lifestyle, she was also a devoted mother and took an interest in charity. She donated to the poor and even tried to implement reforms to help them. Unfortunately, by the time revolution broke out, she had become the perfect scapegoat. Her Austrian background made her an easy target, and propaganda exaggerated her extravagance. She wasn’t an ideal queen, but she wasn’t the heartless villain history has made her out to be.

6. Benedict Arnold Was a War Hero First

Benedict Arnold’s name is synonymous with treason in the U.S., but before he betrayed the revolution, he was one of its greatest heroes. He played a crucial role in early American victories, including the capture of Fort Ticonderoga and the Battle of Saratoga. But despite his successes, he felt underappreciated and was repeatedly passed over for promotion. He also faced financial struggles after spending his own money on the war effort.

Feeling betrayed himself, Arnold eventually switched sides and plotted to hand West Point over to the British. His plan was uncovered, but he managed to escape. While there’s no excusing his actions, his betrayal didn’t come out of nowhere—he was frustrated by how he had been treated. If the Continental Congress had recognized his contributions, he might have remained a patriot instead of becoming America’s most famous turncoat.

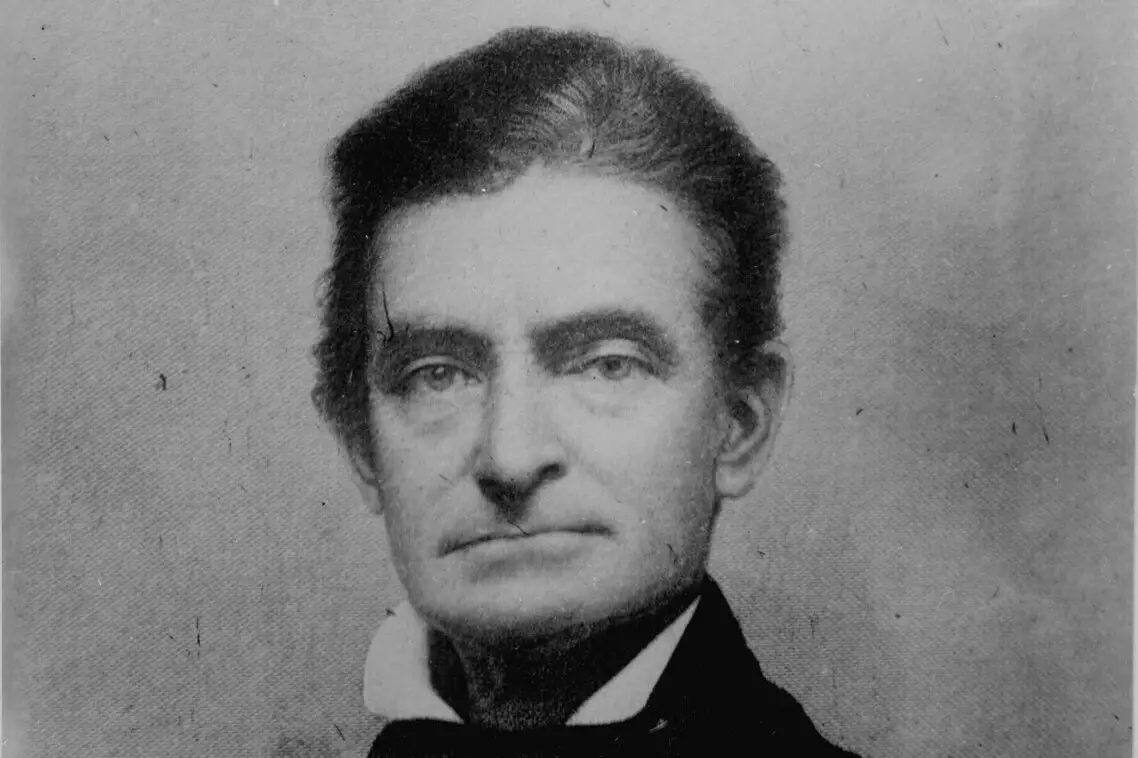

7. John Brown Was Right About Slavery

John Brown is often labeled a fanatic, but his cause—abolishing slavery—was undeniably just. Before the Civil War, he led violent raids against pro-slavery forces, believing that only bloodshed could end the institution. His attack on Harpers Ferry in 1859 was meant to spark a larger rebellion, but it failed, and he was executed. At the time, even many abolitionists thought he went too far.

But history has largely vindicated him. The Civil War proved that slavery wasn’t going to end peacefully. Frederick Douglass later said that Brown’s raid was the beginning of the war that ultimately ended slavery. Though his tactics were extreme, his moral stance was unshakable. In the long run, he was on the right side of history.

8. Emperor Nero Might Have Been Framed

Nero is remembered as one of Rome’s most infamous emperors, accused of tyranny, madness, and even setting fire to Rome in A.D. 64. But there’s no real evidence that he started the Great Fire—he wasn’t even in the city when it began. Ancient historians, who were mostly hostile toward him, likely exaggerated his crimes. In reality, Nero helped rebuild Rome after the fire and even provided aid to displaced citizens. The image of him “fiddling while Rome burned” is pure myth.

Nero also wasn’t as cruel as later writers made him out to be. He promoted arts and culture, reduced taxes, and even advocated for the rights of slaves. His biggest mistake was alienating the Senate, which had a vested interest in painting him as a monster after his death. Many common people actually liked him, and some even mourned him when he died. While he certainly wasn’t perfect, he may not have been the deranged villain history remembers.

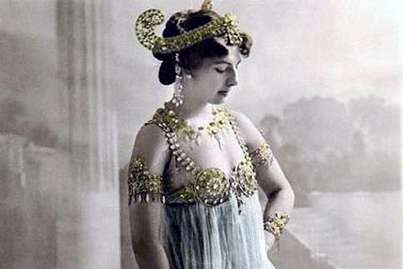

9. Mata Hari May Have Been a Scapegoat

Mata Hari, the famous exotic dancer-turned-spy, was executed for espionage during World War I, but the evidence against her was flimsy. She was accused of passing military secrets to Germany, yet historians now believe she was more of a scapegoat than an actual double agent. The French government was looking for someone to blame for their military failures, and as a foreign woman with a controversial past, she was an easy target.

In reality, Mata Hari may have been involved in low-level intelligence gathering, but there’s little proof she passed on anything important. Her trial was highly sensationalized, and she was convicted more on reputation than facts. Many historians argue that she was more of a victim than a traitor. Her story is a reminder of how fear and politics can sometimes lead to tragic miscarriages of justice.

10. Nicolae Ceaușescu Wasn’t the Worst Dictator

Nicolae Ceaușescu, Romania’s last communist leader, is often remembered as a brutal dictator, but compared to some of his contemporaries, he was far from the worst. Unlike Stalin or Mao, Ceaușescu didn’t oversee mass purges or genocide. His biggest crime was economic mismanagement—he forced austerity measures to pay off foreign debt, which led to widespread poverty. But he also built infrastructure, promoted literacy, and maintained some independence from the Soviet Union.

His downfall came in 1989, when the Romanian people, tired of shortages and oppression, revolted. He and his wife were executed after a hasty trial, more as a symbol of change than due to any specific crimes. While Ceaușescu certainly wasn’t a great leader, he wasn’t uniquely evil either. His harshest policies came late in his rule, and his legacy is more complicated than just “brutal dictator.”

11. Hernán Cortés Didn’t Destroy the Aztecs Alone

Hernán Cortés is often portrayed as the man who single-handedly conquered the Aztec Empire, but the truth is more nuanced. While he played a key role, he had thousands of indigenous allies who helped him overthrow the Aztecs. Many native groups resented the Aztec rule and saw Cortés as a chance to free themselves from their oppressors. Without their support, his small force wouldn’t have stood a chance.

Additionally, the real downfall of the Aztecs wasn’t just warfare—it was disease. Smallpox and other European illnesses wiped out huge portions of the native population, including key leaders. Cortés was ruthless, but he wasn’t the sole architect of the Aztecs’ fall. His story has often been simplified into one of European domination, but it was just as much about internal divisions among the indigenous peoples.

12. Attila the Hun Wasn’t Just a Barbarian

Attila the Hun’s name is practically shorthand for destruction, but he wasn’t simply a savage conqueror. To his people, he was a unifier who brought stability to a nomadic empire that had long been scattered. He kept the Huns strong and organized at a time when the Roman Empire itself was crumbling. From that perspective, he was more of a defender of his people than a villain.

The Romans, of course, saw him differently, painting him as the “Scourge of God.” Yet, Attila’s raids exposed just how fragile Rome had become, and some historians argue he was more a symptom of Rome’s decline than the cause. He demanded tribute, but so did Rome when it was at its height. For the Huns, he wasn’t a villain—he was a leader who ensured their survival.

13. Machiavelli Was More Realist Than Ruthless

Niccolò Machiavelli is often remembered as the man who wrote The Prince, a guide that supposedly champions ruthless politics. The phrase “the ends justify the means” is linked to him, though he never wrote it. His book was really an attempt to describe political reality in Renaissance Italy, a place torn apart by constant wars and treachery. In that brutal environment, being soft could mean losing your throne—or your head.

Machiavelli wasn’t glorifying cruelty, but explaining that leaders had to be pragmatic. He also wrote other works that promoted democracy and civic virtue, ideas that rarely get mentioned. His reputation as a schemer comes from centuries of misinterpretation. In truth, he may have just been brutally honest about how power works.

14. Vlad the Impaler Was Protecting His Land

Vlad III of Wallachia, better known as Vlad the Impaler, inspired the legend of Dracula thanks to his terrifying punishments. Impaling enemies on stakes is about as gruesome as it gets. But his brutality had a purpose: he was defending his small principality against the mighty Ottoman Empire. For his people, he was a national hero who stood up to an overwhelming enemy.

The Ottomans were known for their own harsh tactics, and Vlad’s cruelty served as a warning to invaders. While his methods were horrifying, they kept his enemies at bay and gave his people a sense of security. Today, in Romania, he’s remembered more as a patriot than a monster. His villainy might just be a matter of perspective.

15. Thomas Paine Wasn’t Just a Troublemaker

Thomas Paine was considered radical in his time, often vilified for stirring up revolution with pamphlets like Common Sense. His writings encouraged ordinary colonists to question monarchy and demand independence. Critics saw him as a dangerous agitator, especially in Britain. But without voices like his, the American Revolution might never have gained momentum.

Later, Paine also argued for social welfare, religious freedom, and the abolition of slavery—ideas that made him even more controversial. While many dismissed him as reckless, he was really ahead of his time. His so-called troublemaking was actually a push for progress. History shows he may have been right all along.

16. Mary I of England Wasn’t “Bloody Mary” Alone

Mary I of England earned the nickname “Bloody Mary” for burning Protestants during her reign, but the picture is more complicated. She was trying to restore Catholicism in a country that had swung Protestant under her father, Henry VIII, and brother, Edward VI. Religious violence was unfortunately common in Europe at the time, not unique to Mary. Her actions were brutal, but they were also consistent with the period’s standards.

Mary also worked to strengthen England’s finances and even promoted reforms that helped the navy. Yet her legacy is overshadowed entirely by her persecutions. Elizabeth I, her half-sister and successor, had her own share of bloody crackdowns, but history remembers her more favorably. Mary’s villainous reputation may owe as much to propaganda as to her actual reign.

17. Napoleon Wasn’t Just a Power-Hungry Tyrant

Napoleon Bonaparte is often remembered as a warmonger who plunged Europe into chaos, but he also brought sweeping reforms. He created the Napoleonic Code, which influenced legal systems around the world. He expanded access to education and promoted merit over birthright, breaking down feudal structures. To many ordinary citizens, his rule offered more opportunity than the monarchies that came before.

Yes, his ambition led to devastating wars, but Europe was already a battlefield of shifting alliances. Napoleon didn’t invent conflict—he thrived in a time when it was everywhere. For France, he restored pride after years of revolution and instability. His villainous image may say more about his enemies than his actual legacy.

18. Tamerlane Was Brutal, But He Built an Empire

Timur, better known as Tamerlane, is remembered for leaving piles of skulls in his wake as he expanded his empire across Central Asia. His conquests were undeniably brutal, but they also forged connections between regions that had been isolated. He patronized art, architecture, and learning, turning Samarkand into one of the great cultural centers of the medieval world.

To his enemies, he was a ruthless invader. To his followers, he was a strong leader who created stability in a chaotic time. His empire didn’t last long after his death, but his influence on culture and trade endured. Like many so-called villains, his story depends on where you’re standing.